| FAMSI © 2004: Michael L. Loughlin |

||

|

Recorrido Arqueológico El Mesón Preliminary Results and Observations Analyses of the survey data and recovered artifacts are ongoing; however, some preliminary results of the survey can be presented. A total of 383 individual architectural features or artifact concentrations were identified during the RAM survey (Recorrido Arqueológico El Mesón), a density of 12.3 architectural features or artifact concentrations per square kilometer (Figure 3).

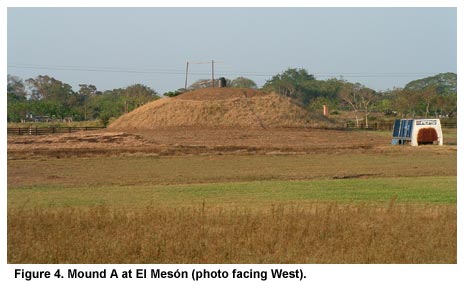

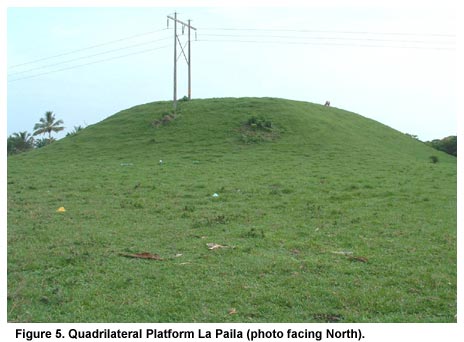

The overall settlement pattern observed in the El Mesón area is characterized as a zone of contiguous settlements with architectural complexes formed from variable patterns of component architectural features including low residential mounds, larger conical and long mounds, large quadrilateral platforms, and artificial bajos (Figure 4, shown above, and Figures 5 and 6, shown below). Some of these complexes feature plaza arrangements. Comparisons of the El Mesón area with other nearby centers in the Gulf Lowlands indicate that the density and arrangement of architectural features is more similar to the Mixtequilla region of south central Veracruz than Tres Zapotes (see Pool 2003a:92; Stark and Heller 1991). Like the Mixtequilla, residential dispersion at El Mesón blurs the boundaries between settlements making the identification of discrete "site" boundaries difficult. The result is that the archaeological record in the area around El Mesón exhibits an almost continuous distribution of architectural features and surface artifact scatters across the landscape.

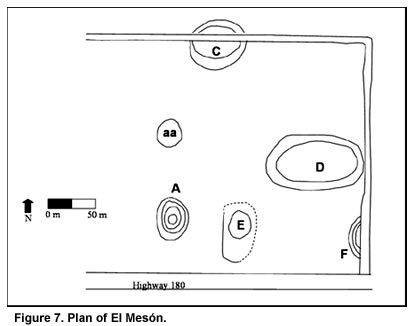

Although the overall settlement pattern for the El Mesón area is more like the Mixtequilla, the formal arrangement of architectural features in the main mound group at El Mesón strongly resembles the layout of the major mound groups at Tres Zapotes. This pattern, which features a plaza bounded by a long mound to the north, a conical mound to the west, and a small adoratorio in the centerline of the plaza, is also present at El Mesón (Figure 7, shown below); however, the scale of construction is greatly reduced at El Mesón in comparison to Tres Zapotes (Pool 2000:150; Sullivan 2002). Pool (2000:150; 2003a:92) has argued that the mound groups that conform to this pattern at Tres Zapotes may have served as seats of authority for factional leaders who shared governance of the center. Given the proximity of El Mesón to Tres Zapotes, and the presence of Epi-Olmec monuments at the site, the replication of the Tres Zapotes mound group pattern may indicate that the El Mesón area was tied politically to the large center, possibly as a secondary center. The reduction in the size of the architectural features may be an indicator of El Mesón’s subordinate position to Tres Zapotes during the Late and Terminal Formative periods. Alternatively, Pool (2003b) has suggested that this replication of this mound group outside of Tres Zapotes may be indicative of emulation of the prestigious center by independent local political leaders.

Diagnostic ceramics recovered from surface collections document a settlement history for the El Mesón area that spans from at least the Middle Formative through the Postclassic periods. This chronology is based on comparisons of El Mesón ceramics with the ceramic sequence developed for Tres Zapotes by Ponciano Ortiz Ceballos (1975) and refined during the Recorrido Arqueológico Tres Zapotes (Pool personal communication). Evidence for Early Formative settlement at El Mesón was scant. Two sherds of Calzadas Carved were recovered during the survey indicating a possible Early Formative component. The first clear evidence of settlement in the El Mesón area dates to the Middle Formative period (800-400 B.C.), based on diagnostic ceramics recovered from 21 locations within the survey area (Figure 8). It was during this period that El Mesón itself was first inhabited. As yet it is unclear if the mounds at El Mesón were associated with the Middle Formative occupation or if they date to later occupations. Additional Middle Formative settlements were located north of El Mesón along the Tulapilla Arroyo. The Late Formative period (400 B.C.-A.D. 100) was a time of important growth for settlements in the El Mesón area. Diagnostic Late Formative ceramics were recovered from 206 locations within the survey area (Figure 9). El Mesón itself expanded during the Late Formative period growing to include settlements on the south bank of the Tecolapan River, and likely served as a small regional center. Settlements also expanded to the north and west of El Mesón. During the Late Formative period, at least two additional areas of civic ceremonial architecture were constructed, La Paila and Chico Loco. These two mound groups featured plaza arrangements with a large quadrilateral platform paired with a conical mound. The Terminal Formative period (A.D. 100-300) was largely a continuation of the Late Formative growth. Diagnostic Terminal Formative ceramics were recovered from 226 locations (Figure 10). In general, the settlement pattern of the Late Terminal Formative is the same as for Late Formative period. Modest expansion of settlement was encountered in the area to the north and west of El Mesón. During the Early Classic period (A.D. 300-600) the growth trend begun during the Late and Terminal Formative periods continued. Diagnostic Early Classic ceramics were recovered from 258 locations within the survey area (Figure 11). Although the overall trend during the Early Classic period is growth, El Mesón itself experienced a decrease in settlement intensity. Settlements expanded to the south of El Mesón and to the northwest of the site in the areas around La Paila and Chico Loco. By the Late Classic period (A.D. 600-1000) both El Mesón and the surrounding settlements were in decline. Late Classic diagnostic ceramics were recovered from 194 locations within the survey area (Figure 12). Although El Mesón itself continued to be occupied, much of the site had been abandoned. Settlements during the Late Classic period continued to concentrate around Chico Loco and La Paila; however the ceramic data suggests that these areas also experienced a decrease in the intensity of settlement. Likewise, at Tres Zapotes populations were declining and the site was largely abandoned during the Late Classic period (Pool 2003b; Pool and Ohnersorgen 2003:25). It is important to note here that the division of the Classic period in the Tuxtlas area is based on a limited number of diagnostic types. This division may present problems in that if ceramic traditions cross phase boundaries, then later time periods may be underrepresented in the distributions. Regardless, the marked decline in the ceramic distributions between the Early and Late Classic periods still indicates that the intensity of occupation in the area was decreasing. Like the evidence for Early Formative settlement, Postclassic diagnostic artifacts were scant in the project area. Five stamped base sherds, one sherd of Texcoco Molded, and three Tula type projectile points were recovered. Given this scarcity of Postclassic materials, no patterning of Postclassic settlement could be identified. |

||

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||