| FAMSI © 2005: Hans Roskamp |

||

|

Pre-Hispanic and Colonial Metallurgy in Jicalán, Michoacán, México: An Archaeological Survey

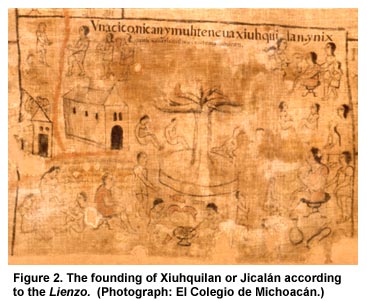

Introduction In addition to the Relación de Michoacán (1539-1541), one of the best known and most widely studied ethnohistorical documents in Michoacán is the Lienzo de Jicalán (Figure 1, shown above). This Lienzo is a pictographic document elaborated and used in the second half of the 16th century as proof of the rights that the indigenous authorities of Jicalán believed they held over several mineral deposits, copper sources and soil-based colorants in the "Hotlands" (Tierra Caliente) of Michoacán. According to the Lienzo, the ancestors who founded this town in remote times were Náhuatl-speaking Toltecs who venerated the god Tezcatlipoca. Born to the east, beyond the coast of Veracruz, where the sun that gives birth to all life rises every day, they had at some moment set out on an arduous migration towards western México that eventually brought them to the area south of the modern city of Uruapan, where they established the so-called Cacicazgo (chieftainship) of Jicalán and initiated their main economic activities: copper-smelting and the elaboration of painted gourds (Figure 2, shown below).

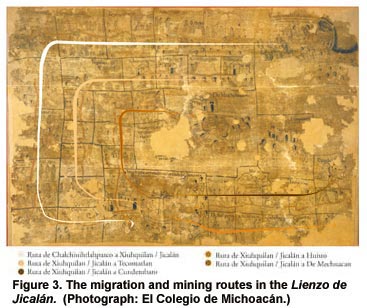

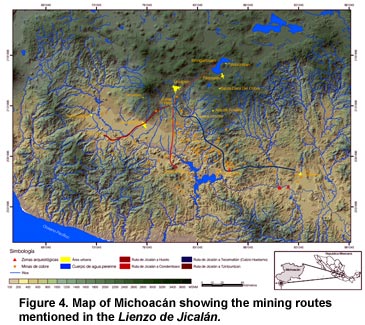

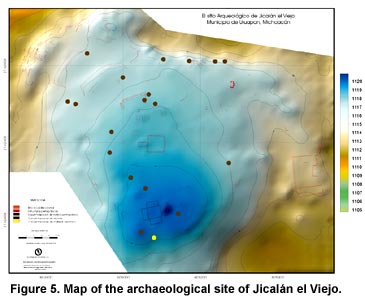

The Lienzo reveals that the inhabitants of Jicalán exploited copper mines located along three routes leading to different areas of the Hotlands. The first led south until it reached the northern shore of the Balsas River, in lands that now form part of the municipality of Huetamo (southeast of Jicalán). The second route followed the Marqués River up to the present dam at El Infiernillo (to the south), while the endpoint of the third route was the Pinzándaro region, on the shores of the Tepalcatepec River (southwest). Although after Jicalán was annexed by the Tarascan Empire in the late 15th century, its residents began to pay tribute in the form of gourds and agricultural utensils made of copper, their rights to the mines were recognized by both the pre-Hispanic kings and their Colonial-era successors (Figure 3 and Figure 4, shown below). 1 While in the Relación de Michoacán the Hotlands appear almost exclusively as an extraction zone for valuable natural resources that were exploited by the Tarascan rulers at Tzintzuntzan, the Lienzo de Jicalán emphasizes the antiquity of the area’s occupation by Náhuatl-speakers claiming to be Toltecs, who had their own worldview and religion and, moreover, were absorbed into the Tarascan kingdom just a short time before the arrival of the Spanish. To a great extent, the visions of the past revealed in these two ethnohistorical documents (the Relación and the Lienzo), fulfilled the function of legitimizing certain rights. For this reason, they must be studied with great care and compared, as far as possible, with other written sources and, above all, with the results of archaeological research. After carrying out a detailed iconological and ethnohistorical analysis of this pictographic document, in early 2003 we initiated a project designed to survey, take an inventory and map the archaeological site of Jicalán el Viejo, which has been identified as the key locality represented in the history narrated in the Lienzo (Figure 5, shown below). The present report begins with a summary of the preliminary results of our early fieldwork and finalizes with some reflections based on comparisons of the archaeological data recovered with available (ethno-)historical information.

| ||

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||