| FAMSI © 2005: Hans Roskamp |

||

|

Pre-Hispanic and Colonial Metallurgy in Jicalán, Michoacán, México: An Archaeological Survey

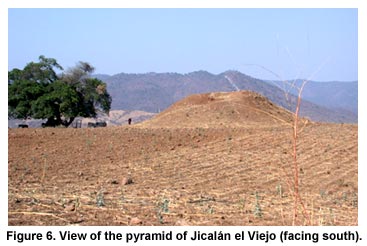

Jicalán el Viejo: An Archaeological Survey The most notable architectural remains are found in the upper (center-south) area of the site and include a small, square, stepped pre-Hispanic pyramid (Figure 6, shown above) measuring approximately 22 x 22 meters (72 x 72 feet), with a height of 5 m. (16.4 ft.). On one side of this pyramid, we discovered other remains. Though seriously deteriorated and barely visible, they seem to represent three structures arranged in the form of a U (each about 22 m. [72 ft.] long by 12 m. [39.4 ft.] wide). It seems probable that they formed one complex with the pyramid itself. In the structure located to the west, we found broken stone slabs and very small bone fragments that indicate burial sites. These materials had been strewn on the surface due to recent activity by plunderers (Figure 7, shown below).

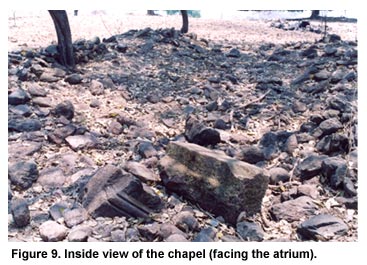

Some 175 m. (575 ft.) to the north but at a lower elevation, there is a 24 x 12 m. (78.7 x 39.4 ft.) elongated structure with an access on the eastern side that opens upon a large, almost square, open space (42 x 40 m. [137.8 x 131.2 ft.]) and is known locally as the "Temple". The form and size of this edifice, together with our discovery of large pieces of carved limestone that once formed part of a façade, certainly suggest that this was a small chapel complete with atrium (Figure 8 and Figure 9, shown below). This religious building was located in the very center of the site, on the elevated area that corresponds to the pre-Hispanic settlement, exactly where the main indigenous temples had once stood, thus symbolizing the triumph of the Christian God over earlier autochthonous deities and revealing that the elevated area of the site continued to be dedicated to religious cults.

Though identifying the large structures mentioned above presented no great problem, there are numerous vestiges whose nature it is difficult to interpret without actual excavations. Perhaps 50 m. (164 ft.) north of the "Temple", still in the elevated zone but on a downward incline, we found another edifice that also appears to form a U, though it is not completely symmetrical. Its maximum width is 22 m. (72.2 ft.) and it has two extremities 12 and 17 m. (39.4 and 55.8 ft.) long, respectively, and about 7 m. (23 ft.) wide. To the east, there is another important building, this one in the form of an L, with extremities that measure as follows: 28 x 7 m. (92 x 23 ft.) and 21 x 11 m. (69 x 36 ft.), respectively. Unfortunately, in these two cases the remains are insufficient to determine if they are of Pre-Columbian or Colonial construction. Barely 40 m. (131.2 ft.) to the north and still heading downwards, we found a man-made incline (ramp) 74 m. (242.8 ft.) in length that serves as an access to another terrace or small inclined plain, located at a lower level. At one end of the upper part of this incline we detected the remains of walls arranged in what appear to be habitations, four of which were about 10 x 4 m. (32.8 x 13.1 ft.), while the other two measured 17 x 4 m. (55.8 x 13.1 ft.), and 15 x 4 m. (49.2 x 13.1 ft.) respectively. The latter was located a few meters to the south and marked by the presence–both in its interior and exterior–of large amounts of slag from copper smelting. So far, this is the only place at the site where we have found this type of material in direct association with a structure.

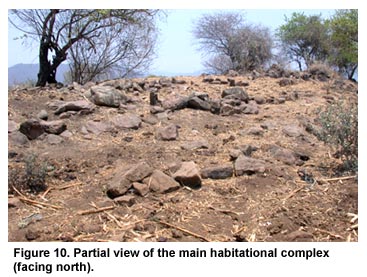

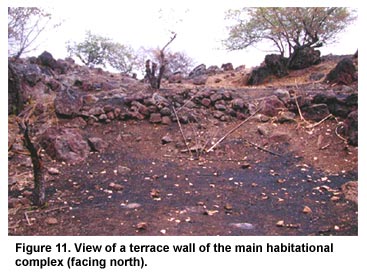

A second incline, this one some 121 m. (397 ft.) long, was found 100 m. (328 ft.) to the northwest. It marks the boundary of a lower terrace. A third such ramp (96 m. or 315 ft. long) is located some 60 m. (197 ft.) further northwest, but at a somewhat lower elevation. At short distances–perhaps 60-70 m. [197-230 ft.]–to the west, north, and northeast and still descending towards the northern edge of the platform, we identified several apparently inhabited terraces with remains of walls that formed rooms (Figure 10, shown above, and Figure 11, shown below).

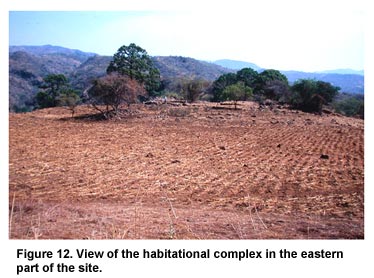

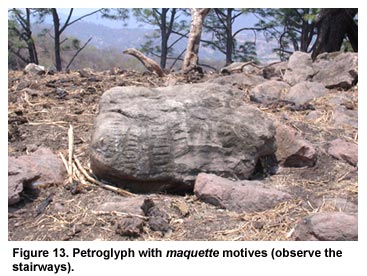

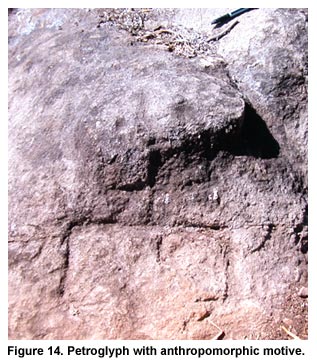

This complex is the largest and most important of all, but the eastern end of the platform also revealed a significant zone of terraces with habitations showing the same features (Figure 12, shown above). A third, much smaller, compound is located on the center-north edge of the site. Our attention was drawn especially to these lower areas at Jicalán el Viejo, because of the presence there of petroglyphs, most of which seem to pertain to the style known as maquettes (Sp. maquetas), as they represent stairways, buildings and some type of well or, perhaps, springs and rivers (Figure 13, shown below). Three of these stones bear geometrical designs, while three others have anthropomorphic images and one revealed an iconographic element in the form of a horseshoe (Figure 14, shown below).

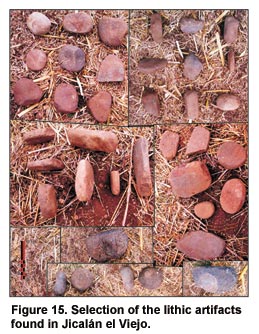

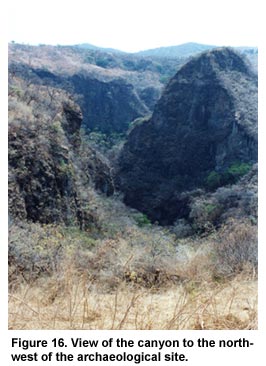

The site produced large quantities of lithic artifacts associated with milling or grinding: the typical metates, manos, molcajetes (three kinds of grinding stones, normally identified by their Spanish names), an axe and several peculiarly-shaped stones (Figure 15, shown below). The latter are rather fine river rocks that may have been used for polishing. A fine, smooth stone somewhat larger than a typical metate but made from the same material, may also have served this purpose. Among the most abundant artifacts were rectangular stones with round holes on each side, stones of a similar shape but flattened and with only three sides, also with holes, and round stones with small orifices (that do not perforate the stone), in the center or towards one end. Without discounting other possible uses, it is probable that many of these artifacts were used in copper-smelting or in elaborating painted gourds, two of the basic occupations of the inhabitants of Jicalán mentioned in the Lienzo and other historical sources. 2 It also seems that various artifacts catalogued as "domestic utensils" were re-utilized for other purposes. One of the metate-type stones found at Jicalán has a square figure in the center and may have been used as a mold for producing axes or other copper utensils. The obsidian remains include small cores, prismatic blades, arrowheads, scrapers and chips, etc. In addition, two fragments of silex or quartz were found, one of which was a kind of ornament in the form of a flower petal. With respect to ceramics, it is worth noting that we found only fragments (sherds) that belong to a monochrome variety and clay spools. So far, we have found no diagnostic pieces that would allow us to propose a tentative date for the occupation of this site. Jicalán also stands out because of the large deposits of slag found, especially, at high and middle elevations, but also near the small complex of structures in the north-northeast. The pieces of slag residue found at the site vary greatly in size, thickness and texture. Some samples are being analyzed by Blanca Maldonado (Pennsylvania State University) and compared with similar materials that she discovered at the archaeological site of Santa Clara del Cobre. Preliminary results suggest that the slag at Jicalán resulted from chalcopyrite processing and that the indigenous specialists there employed a highly-sophisticated, efficient reduction method. 3 Future survey pits and excavations will provide additional information on the nature and development of the metallurgical activities that took place at this site. The detailed comparison of these results with findings from ongoing excavation projects at other smelting sites, such as the aforementioned Santa Clara del Cobre site in Michoacán and El Manchón in the Sierra Madre of Guerrero (an intriguing zone with only pre-Hispanic occupation), should prove very interesting. 4 It seems likely that most of the agricultural fields tended by the folk at Jicalán were located in the terraced areas. The sources of water needed for farming existed in nearby, relatively accessible canyons to the north, where cultivation may also have taken place and other edible vegetable products could be gathered. Today, residents exploit waterholes located at the northern base of the platform, where there is a small lagoon that is not mentioned in Colonial-era sources. One final relevant aspect of this archaeological zone is its strategic location: it constitutes a natural fortress that is difficult to access and is protected by deep canyons, especially to the south and west (Figure 16, shown below). We should also mention that it occupied a strategic position on the frontier between the Hotlands (to the south) and the Sierra Tarasca (to the north).

| ||

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||