| FAMSI © 2004: Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Analysis of Archaeological Artifacts from Cotzumalhuapa, Guatemala The Cotzumalhuapa Causeways Description The map in Figure 2 summarizes our current knowledge of Cotzumalhuapa. The monumental compounds of El Baúl and Bilbao stood on the northern and southern parts of the city. Both are large acropolis-type platforms sustaining numerous buildings, with large concentrations of monumental sculpture. The enclosed and elevated layout of El Baúl suggests a defensive function, while Bilbao appears to be more open and accessible. El Castillo is a smaller but significant concentration of monumental architecture and sculpture, dominated by a ten-meter high mound that overlooks what appears to be an open plaza. Another important ceremonial compound was probably located at Golón, on the southeastern part of the city. No monumental architecture is visible today, but an important group of monumental sculptures appeared in this sector (Chinchilla 1996a: 269-272). These compounds were linked together by a system of stone-paved causeways identified by project excavations between 1997 and 2002. The causeways were named after early pioneers of Cotzumalhuapa archaeology. The following causeways have been identified so far:

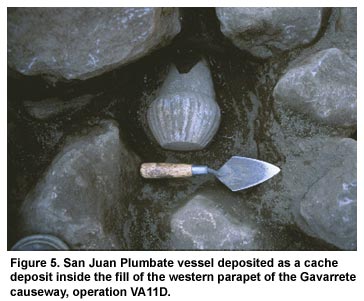

The Thompson causeway suggests that there may be numerous other small causeways extending to outlying settlements, but their small size makes their detection difficult. Interestingly, there appears to be no direct avenue joining El Castillo with El Baúl, but its existence cannot be absolutely discarded. Ceramics recovered from a large portion of the Gavarrete causeway were analyzed. The typological analysis was carried out using the typology of Pacific coastal ceramics developed by Frederick Bove, José Vicente Genovez, and Sonia Medrano (in preparation). This typology is partly based on Lee Parsons’ (1967) study of ceramics from his excavations at Bilbao, with significant modifications based on previous excavations at Cotzumalhuapa and elsewhere on the Pacific coast. Based on their analysis, Bove and his collaborators developed a new chronological sequence for Escuintla, supported by a series of radiocarbon dates (Figure 3; Chinchilla, Bove, and Genovez n.d.). Causeway excavations were largely limited to the upper layers or recent soils and sediments above the causeway pavements. Therefore, the materials recovered do not necessarily provide dates for the construction of the causeways. They may include considerable amounts of materials that were transported by natural erosion and human agents from other locations, and redeposited above the causeway pavements. Yet, the composition of the sherd collections is largely consistent with patterns observed elsewhere at Cotzumalhuapa, and it seems probable that they reflect the composition of ceramic assemblages in the general area traversed by the causeways. Typically, they include small amounts of Postclassic sherds, which are restricted to the most superficial levels. Middle to Late Classic materials are overwhelmingly dominant in every assemblage. Diagnostic sherds from the Formative and Early Classic periods are also found occasionally. An important problem in Cotzumalhuapa archaeology involves the discrimination of Middle and Late Classic materials. As first observed by Parsons (1967: 142-143), numerous Middle Classic types continue into the Late Classic period. These include numerically important types such as Tiquisate and Perdido. However, they are mostly found mixed with Late Classic diagnostics such as Diamantes, San Andrés, and San Juan Plumbate. Therefore, any particular context that includes Late Classic diagnostics is considered to be Late Classic in date. Only those rare contexts that include no Late Classic diagnostics are considered to be Middle Classic. Operation VA11D (Figure 4) may serve as representative of the ceramic assemblages recovered from excavations in the Gavarrete causeway. This operation is located 110 meters south of the bridge on the Santiago River, on the side opposite to El Baúl. The operation included two trenches (respectively 2×8 m and 2×6 m), that revealed the eastern and western sides of the causeway. These trenches were divided in 2×2 m excavation units. At this point, the causeway rises from the river gorge to the reach level of the terrain above. The natural terrain was substantially leveled and the excavation trench revealed a retaining wall built on the western side of the causeway, which still rises 60 cm, with three courses of stones preserved on the outer (western) side. On the eastern side, the causeway adjoins a natural elevation that was probably cut to level the causeway, and provided with a rough stone facing. Two additional 2×2 m pits (units S10 and V10) were excavated 8 m south of the previous trenches. They revealed the causeway pavement and its western edge. At this point, there was no further need for substantial leveling, and therefore, the causeway is delimited by a single line of roughly aligned stones. Tables 1-3, shown below, summarize the ceramic contents of these excavations. As noted, these materials were found within the thick soil layers above the level of the causeway pavements, and therefore, do not necessarily coincide with the date of their construction. Nevertheless, they provide a general dating for the occupation of the area. Formative sherds were entirely absent, while Early Classic materials were minimally present. Diagnostic materials from the Middle Classic period are scarce, while the dominant component of every excavation level consisted of Middle to Late Classic materials. Late Classic diagnostics formed the second largest group, but their abundant presence suggests that these lots are largely of Late Classic origin. A small presence of Postclassic materials in the uppermost excavation levels most likely derives from thin settlements of that period in the surrounding area, whose presence postdates the abandonment of the causeway system and the city as a whole.

A particularly important find was a San Juan Plumbate jar (Figure 5, shown above) with globular, striated body, and incurving neck, that was deposited inside the fill of the retaining wall of the Gavarrete causeway. This cache vessel allows a secure dating of this construction to the Late Classic period. San Juan Plumbate is one of the major makers of the Late Classic period at Cotzumalhuapa and elsewhere on the Pacific coast (Thompson 1948; Parsons 1967). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||