| FAMSI © 2004: Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

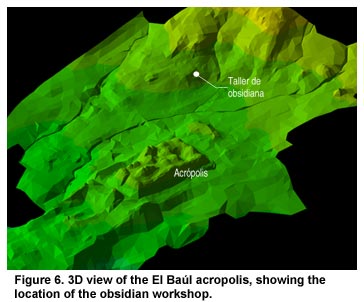

Analysis of Archaeological Artifacts from Cotzumalhuapa, Guatemala The El Baúl Obsidian Workshop Summary Description of Excavations The El Baúl obsidian workshop was first identified and test excavated in 1996 by Sonia Medrano, who observed an extensive area with dense surface concentrations of obsidian debris, located about 200 meters north of the El Baúl Acropolis (Figure 2, and Figure 6, shown above). Debitage concentrations extended over the slope of a low, rock-strewn promontory that was probably ill-suited for habitational purposes, a condition that may have influenced its selection as a dump. Field research in 2002 focused on this area, beginning with a series of 81 shovel tests placed along a ten-meter grid that covered the entire area. Significant samples of obsidian were recovered from these shovel tests, allowing to quantify the density of obsidian throughout the debitage area and to define its approximate limits (Figure 7). The major concentration covers an area of 3120 m2, covering the top and the eastern slope of a natural promontory. The highest concentrations are found at the rock-strewn top of the promontory, where a shovel test revealed a maximum density of 40,526 obsidian fragments per cubic meter, recovered by sifting materials through a 1/4 inch mesh. Very high densities were also found at selected places along the promontory slope. Excavations were carried out at two locations:

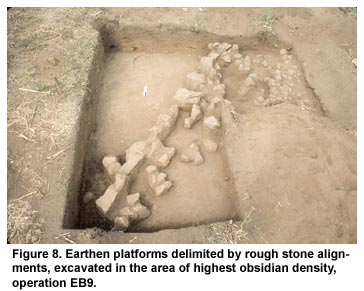

(a) Possible Workshop Platforms Excavations on the promontory slope revealed simple platforms with earthen floors lined with rough stones (Figure 8, shown above, and Figure 9). The location of these platforms amidst the major concentrations of obsidian debitage suggests that they were not habitational in function, and there is a possibility that they may have served as work places for the artisans involved in the industry. A stratigraphic pit (Suboperation P31) excavated by the edge of one of these platforms revealed a series of primary deposits of obsidian refuse (Figure 10, shown below, and Figure 11). Unlike the indistinctly mixed materials recovered in upper excavation strata, these deposits appeared to be the result of specific depositional events, which were sealed relatively fast by the construction of the platforms above, and thus remained undisturbed. Analysis of these deposits is particularly important for the study of the ancient obsidian industry. The P31 stratigraphic pit continued below these deposits to a depth of 3.78 meters, revealing volcanic ash layers derived from the adjacent Fuego volcano. Obsidian debitage continued below these ash layers, suggesting that the area was used as a refuse deposit for a prolonged period.

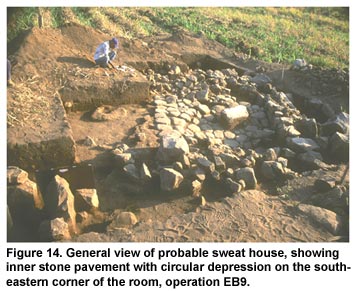

(b) Possible Sweathouse Further excavations located 30 meters south from the former, revealed architectural features that merited extensive inquiry to determine their conformation and association with the obsidian debitage deposits. Excavations revealed a one-meter high, stone-faced leveling terrace built against the natural slope, providing a foundation for a small but elaborate stone-walled room provided with a finely laid stone pavement in the interior (Figure 12, and Figures 13 and 14, shown below). This is no ordinary trait, since stone pavements found in previous excavations commonly cover exterior surfaces. Moreover, this pavement was built with a concave depression that reached its bottom at the southeastern corner of the room. The precise function of this room remains in doubt, but there its size and conformation suggest that it may have functioned as a sweathouse, with the concave depression serving as an inner drainage system. Moderate concentrations of burned sherds and ashes, associated with a concentration of rough stones suggested that this corner of the room was also used as a fireplace. The western side of the room is devoid of a stone wall, but the excavations revealed the southern façade of an elevated platform that must have closed this side of the possible sweathouse. There are indications that this was part of a larger architectural compound, but it was not possible to extend excavations to other adjacent buildings. Therefore, the question remains whether this was part of a domestic compound or otherwise. Yet, the presence of such elaborate architecture next to the obsidian dump is intriguing, because of the possibility that it may be related with the industry. High concentrations of obsidian debris were recovered from the structural fill, indicating that its construction involved reuse of earth from the dump area. (a) Possible Workshop Platforms The P31 stratigraphic pit provided significant information for dating the utilization of the workshop dump. The pit went down 2.40 m below the surface, plus an additional 70 cm deep shovel test (level 17) that explored the lowermost levels. Table 4 summarizes the ceramic contents of this pit.

The major stratigraphic units identified were the following:

(b) Possible Sweat House Collections recovered from the possible sweat house are predominantly Middle to Late Classic, but they also contain a significant amount of Postclassic sherds, including Santa Rita Micaceous and Sumatán (Parsons 1967: 157-158). Importantly, there is also a small amount of early types such as Nahualate, Colojate, and Achiguate, that may date to the Terminal Formative or Early Classic periods (Medrano 1993). Excavations on the western side of the possible sweat house revealed a tamped earth floor that may have been a corridor between the sweat room and the adjoining elevated platform. A concentration of large sherds deposited on this floor proved to include mainly large censer fragments, suggesting that ceremonial activities were carried out in this structure. A cache found underneath this floor contained a cylindrical vase covered with a small black bowl (see below). Excavations included a stratigraphic pit (Suboperation M13), excavated through a tamped earth floor located on the western side of the structure. The pit penetrated to a depth of 2.20 m below the surface. Table 5, below, summarizes the ceramic contents of this pit. As expected, Postclassic diagnostics were limited to the uppermost excavation levels. Terminal Formative–Early Classic sherds were also recovered in small numbers, mixed with the overwhelmingly dominant Middle to Late Classic materials. Importantly, this pit revealed no evidence of earlier constructions below the tamped earth floor associated with the sweat house. Late Classic diagnostics, including San Juan Plumbate, were present down to the lowest excavation levels. Therefore, it may be concluded that the structure had a single construction episode, which included substantial leveling and modification of the natural terrain.

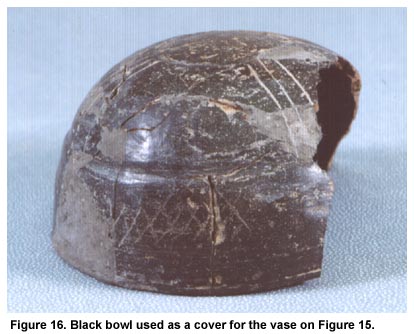

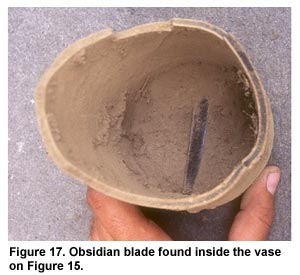

(a) Cache associated with possible sweat house A probably dedicatory offering found under the tamped earth floor on the west side of the sweat house room, consisted of a cylindrical vase of the Cueros type, characterized by its smooth brown slip, with a thick red band around the middle section of the vase (Figure 15, shown above). Fragments of a small black-slipped bowl with incised decoration were found inside the vase, suggesting that it was placed as a cover for the vase, in inverted position (Figure 16, shown below). Such pattern has been previously documented in cache deposits at Cotzumalhuapa.

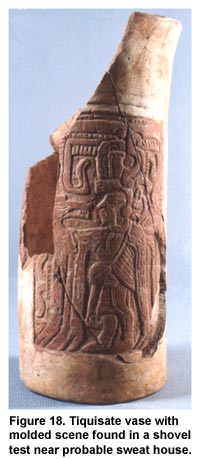

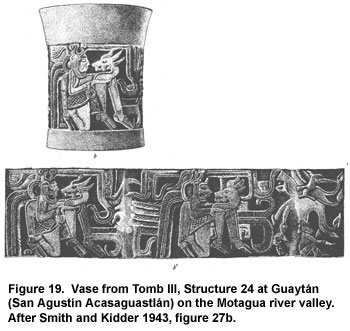

A complete and unused obsidian blade was found inside the vase (Figure 17, shown above), another feature that has been documented in several cache vessels at Cotzumalhuapa. The presence of these blades inside cache vessels suggests that they were used during the dedicatory ceremonies that led to the deposition of these vessels. One possible explanation is that they were used in bloodletting rituals performed during such ceremonies. Blood was presumably spilled inside the vessels, and the instrument used to let blood was finally deposited inside the same vessels. The consistent appearance of unused obsidian blades in cache vessels allows an interesting hint into the ritual activities performed at Cotzumalhuapa. (b) Tiquisate vase with molded scene One shovel test located 15 meters west of the possible sweat house revealed a Tiquisate cylindrical vase, with mold-made scenes on opposite sides, both with soft red painting (Figure 18, shown above). The vase may have been part of a cache offering, perhaps associated with another structure, but the location was not further excavated, and therefore, the vase’s context was not completely documented. Nevertheless, the vase has proved to be a very important find, on account of two issues: (a) This is one of only a handful of Tiquisate vases with molded scenes that have a known archaeological provenance. A number of unprovenanced vessels are also known from private and public collections, but overall, this important type of vessel remains poorly documented. (b) The iconography of this vase relates with a number of unprovenanced vases, and also with a vase that was deposited as a funerary offering in a tomb at the site of Guaytán, on the Motagua river valley (Figure 19, shown below; Smith and Kidder 1943, figure 27b). With its distinctive Tiquisate slip, the El Baúl vase suggests that the entire group of vases originated on the Pacific coast. The iconography of this group of vases concentrates on the capture of a deer, performed by one or two individuals. Both panels on the El Baúl vase show a standing man embracing a long-tailed deer, recognizable as such by their short antlers and the shape of their hoofs. A black vase from the collection of the Popol Vuh Museum shows an identical scene, oriented in opposite direction (Figure 20). Other vases in this stylistic group show more complex versions of the story. On the Guaytán vase, the scene appears as a continuous band that includes two kneeling individuals, each holding a deer, plus a tree with a bird perched on top and a small animal, possibly a monkey, seated at its base. Other vases that are related stylistically and iconographically include K1378, K1605, K3235, K4599, and K6397. Some of them include additional elements, such as a large reptilian monster that appears on vases K1378 and K6397. A thorough iconographic analysis of these vases escapes the constraints of this report. However, it should be noted that the subject of men capturing deer finds parallel in Lowland Maya iconography, sometimes involving the Hero Twins (Coe 1989; Braakhuis 2001; Chinchilla 2003). Annex I includes a summary of the preliminary results of the analysis of obsidian from the El Baúl, by Edgar Carpio Rezzio (in Spanish). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||