| FAMSI © 2005: Patricia Plunket and Gabriela Uruñuela |

||

|

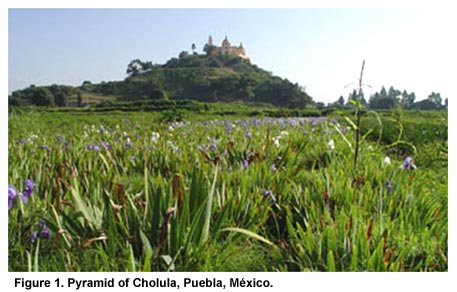

Dating Cholula, México Introduction Although Cholula is considered to be one of the major cities of prehispanic México, it has been the subject of relatively little archaeological work because almost all of the ancient settlement lies buried beneath the modern city. Most research has focused on its Great Pyramid, the largest Pre-Columbian structure in the Americas, but the results of these projects have never been published in detail (López et al. 1976; Marquina 1970b, 1975, 1981; Messmacher 1967; Noguera 1937, 1954, 1956; Romero 1935), leaving doubts about its initial configuration and the dating of the various construction stages (see interpretative attempts in McCafferty 1996a and b). Traditionally, the chronology of Cholula has depended on temporal sequences developed for sites in the Basin of México, and until recently few absolute dates from archaeological contexts were available (see Plunket and Uruñuela 1998b, 2002; Siebe et al. 1996; Suárez 1995). Most minor excavations that have taken place in response to development projects have not been published and no comprehensive interpretive overview of this archaeological research is currently available. Because of this situation, it is difficult to understand the origins of urban Cholula and assess the relationship between the city and other settlements in the Puebla-Tlaxcala Valley or in greater Mesoamerica. The "Dating Cholula" project was designed to initiate the development of an independent chronological sequence for Cholula based on radiocarbon dates from excavated archaeological contexts. In particular, we wanted to explore the possibility that the monumental architecture of the site developed–at least in part–as an adaptive politico-religious response as people sought to cope with the ecological, social, political, economic, and ideological conflicts that certainly developed in the wake of a huge volcanic eruption of the Popocatépetl volcano, which took place around the middle of the first century A.D. This spectacular event deposited 3.2 km3 of pumitic lapilli over an area extending at least 25 km east of the crater; shortly thereafter, lava flows covered close to 50 km2 of the eastern piedmont of the volcano with between 30 and 100 meters of rock that dammed and diverted drainages, altering the surface hydrology of the western Puebla valley (Panfil 1996:16-20).

We have focused heavily on dating of the earliest construction phases of the Great Pyramid that are exposed in tunnels excavated by Ignacio Marquina (1970a, 1981) in order to provide a chronological framework for the first monumental architecture in the ceremonial heart of the emergent city. In addition, we have obtained samples from various other contexts that have become available to us through test excavations and rescue work (López et al. 2002a and b, 2004a and b; Plunket and Uruñuela 2002). This second group of dates is important since it can be used to anchor the ceramic assemblages in time. "Dating Cholula" forms part of the Tetimpa Project whose primary goal has been to study the impact of volcanic activity on the western Puebla Valley. Up until recently, most of our work has centered on the Formative village of Tetimpa, which was buried under the pumitic ash deposited in the first century A.D. The research described in this report represents an attempt to expand our knowledge beyond the immediate boundaries of the territory directly affected by pyroclastic materials and look at a major settlement that must have received refugees at the same time that it had to deal with significant environmental consequences. Dating different areas and occupations within Cholula can help us develop before and after views of the city which will be of central importance to any consideration of the regional effects of the natural disaster. Additionally, we have sought to address the chronology of the Classic-Postclassic transition since Siebe and his colleagues (1996) have suggested that Cholula and its region were impacted by a second major volcanic eruption, sometime in the eighth or ninth centuries (see also Panfil 1996). |

||

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||