| FAMSI © 2004: Jorge Ramos |

||

|

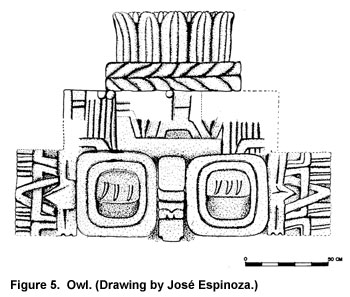

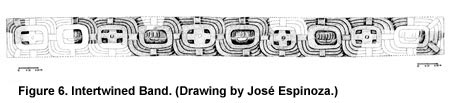

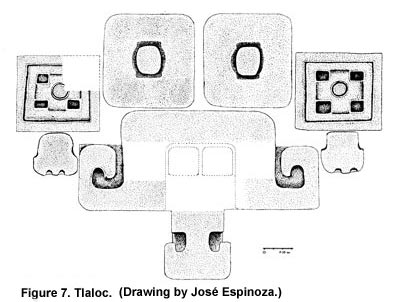

Research on Temple 16: An Ongoing Imagery Reconstruction of Temple 16, Copán, Honduras Fragment Analysis and Rearticulation of Sculpture Mosaics One of the dominant figures that once embellished the Temple 16 façade is the image of an owl. Its partly closed eyes are typical of those of the Witz images on Temple 22 and other freestanding monuments at Copán. The rings around the eyes led Stone (1990) to relate it to the Mexican rain god Tlaloc. In fact, the trapeze and ray iconographic element that adorns its wings makes the image comparable with the Tlalocs depicted on the Nun Complex at Uxmal, Northern Yucatán (Foncerrada de Molina 1965, fig. 27; Schele and Mathews 1998:273, fig. 7.24.a). It is well known that owls are not well represented at Copán; they are even rarer in Classic Maya art. However, the protruding beak projecting downward and the double ball at its end identify this figure with the owl. Similar imagery can be found at Teotihuacán and in Late Classic Maya Teotihuacán-derived iconography (Winning 1948; Grube and Schele 1994). Although not abundant in the Temple 16 sculpture sample (some in pile 28), the paw motif was likely an iconographic attribute of this owl. Rope is common in the motif repertoire of Temple 16. This motif was excavated from all of the investigated sides of the structure. Although still lacking rearticulation and iconographic context, it was associated with war by the PAAC team working on Structure 10L-16; a theme supported by other motifs on the building (Agurcia et al. 1996; Stone 1990; Stone et al. 1996). This season, I noticed through the fallout maps a similar distribution of ropes and plumes and their close association with owl pieces around the building. In addition, during fitting experiments, it was found that arrangements of the plume motif are comparable to that of the rope motif; this discovery, added to the similar carving style and size proportions, suggests that both the rope and plumes were part of the repeated owl images on the building. As my sculpture analysis shows, it is quite possible that the owl on Temple 16 was displayed in the same manner as the macaw on the late Classic ballcourt in the great plaza (B. Fash 1992, fig. 3); with its tail visible and projecting upwards. However, the tail of the owl on Temple 16 had its plumes tied with a rope (Figure 5). Similar examples are found in the architectural imagery at the site of Uxmal (Foncerrada de Molina 1965, fig. 4 and 36). At Teotihuacán, the owl commonly appears in the context of war (Winning 1987a:85, 88). According to Taube (1998), the element on the tip of the beak of the owl could be a human heart. Therefore, war and sacrifice may be emphasized by this image on Temple 16 and other Maya sites (Grube and Schele 1994). The owl of 1.90 m width and 0.9 m height was depicted at the center and corners at the level of the upper section of the first floor. 5 A peculiar motif uncovered on the north and south sides of Structure 10L-16 was the so-called intertwined band with alternating Kan Cross and owl eyes (Agurcia 1996:191; Stone 1990; Taube 1998). My research indicates that this motif, of only 0.45 m high, covered one-third of the length of the north and south façades (Figure 6). It probably laid upon the medium molding of the first floor in a central position. This impressive band, 5.3 m long, likely served as a resting place for the owl, which was depicted a bit higher. Lintel 3 of Temple IV at Tikal features a curving serpent on top of a temple doorway framing the figure of victorious Yik’in Chan Kawil ruler, who stands inside the temple (Harrison 1999:153, fig. 94); a bird, possibly an owl, rests on top of the serpent with extended wings. A rope with alternating discs representing Kan Cross and owl eyes (Taube 1998) seems to be a feasible interpretation for this band since there are no other iconographic elements that could support another explanation. An interlocking eye motif formerly displayed on the Late Classic Temple 21 at Copán (the "Obsidian house" –W. Fash and B. Fash 1989, fig. 8; 1992, fig. 17) depicts the same type of rope as found on Temple 16. The rope on Temple 21 is less elaborate and lacks the Kan Cross. Aside from Copán and some Maya sites in Northern Yucatán (Uxmal), Teotihuacán is the only place where interwoven bands are portrayed. At Teotihuacán, the motif is in some cases a depiction of the plumed serpent. The body of the serpent is further covered by a range of different iconographic attributes such as cut shells 6 (Séjourné 1966:258, fig. 146), Kan Cross 7 (ibid, fig. 90), warrior helmets 8 (Séjourné 1966, fig. 32), and others 9 (Pasztory 1997, fig. 4.8). An interwoven serpent is a common theme depicted at Teotihuacán10 (Pasztory 1988: fig. III 16; 1997: fig. 11.4) and at the site of Uxmal, and Chichén Itzá in Northern Yucatán. The best representative example that recalls the Temple 16 motif is the one depicted on Mural 3 inside the Room 2 of the Tepantitla complex (LaGamma 1991, fig. 6). Although there is not enough supporting evidence, aside from the interwoven rope (serpent?), to argue for a serpent motif on the Temple 16 façade, we cannot rule out this possibility. It is possible that the serpent mouth depicted on the inside of the western room of the building could be in some way related to the exterior imagery. The pervasive presence of Teotihuacán imagery on Temple 16 might support this hypothesis. The Postclassic Maya codices, the Madrid and Dresden, offer some examples of celestial serpents carrying on their bodies Kan Crosses, along with other signs (de la Garza 1984: fig. 12). During excavations, archaeologists working at Temple 16 uncovered a variety of images then identified as Tlaloc (Agurcia et al. 1996; Agurcia and B. Fash 1997; Taube 1998). From around 1,310 sculpted fragments recovered during excavations, they put together a giant Tlaloc head. On the basis of archaeological evidence, Stone (1990:9) noted that at least 12 (two on each façade and one in each corner) of these representations decorated the lower portion of the temple. In addition, they uncovered a portion of at least two of the figures in situ on the north side of the structure, an event that led to the partial union of the images. Based on the numerous representations of this deity on the building, and the analogy of the Popol Vuh, B. Fash (1989:67) labeled Temple 16 as the "Tlaloc House". In 2003, PRIT-16 sought to complement the configuration and dimensions of this Tlaloc mask. One of the features observed in the sculpture sample was the large number of the Kan Cross motifs. An even representative sample was found on all the excavated sides of the structure. Almost the same pattern was observed for the dangle motif. I took out all the pieces pertaining to one of the Tlaloc masks and rearticulated the mask adding the Kan Cross on the sides of the mask and attaching the dangle at the base of the KC; the Kan Cross and the dangle formed the ear spool of the Tlaloc (Figure 7). All the Tlaloc depictions at Temple 16 and other Late Classic monuments at Copán are portrayed associated with Kan Crosses as ear flares. The Kan Cross is an iconographic attribute of Tlaloc in Teotihuacán imagery and is even considered as its denomination glyph (Taube 1998; Winning 1987:65, 66, fig. 1a-1c, 3a-3d). Another recurrent motif found in close association with the Tlaloc images is a piece with one of its ends in a curved form; this piece is very similar to the pieces from the eye of the same Tlaloc, but it certainly is not an eye. It is likely that this motif was part of the mouth–the upper part of the rolling fangs on the sides of the mouth. I also propose that the mask, as with the other representations, was depicted with upper incisor teeth and lacking the lower maw; with these elements, the mask reaches 2.50 m in width and 1.40 m in height, an adequate dimension to accommodate the rest of the images on the wall. The Tlaloc is depicted in a plain style, even simpler than the Tlaloc masks represented in the pyramid of the same building and on Temple 21. The bas-relief was applied only to some portions (fangs, tongue, and ear flares). The entire figure, however, lacking the lower maw and portrayed with death features, is more dominant than the other Tlaloc representations. In addition, the number of the masks (12) and their size emphasize the importance of Tlaloc imagery for Yax Pasah. Moreover, other small Tlaloc heads (0.25/0.30 m high) discovered by Maudslay (1889-1902) decorated the building; the tenon or projecting element in the back of the pieces indicates they were prepared to be on the façade. Teotihuacán imagery displayed on the temple symbolized the social memory or past connections with that great Mesoamerican metropolis. Stuart (2000:502-504) contends that Teotihuacán was the original home of the founder of Copán, Kinich Yax K’uk’ Mo’ (KYKM). In the Iconography of Copán, he is always featured in Teotihuacán costume (Sharer 2003). Teotihuacán was not only the original place of KYKM, but the Tollan for many Mesoamerican culture groups including the Aztecs (Boone 2000a; W. Fash and B. Fash 2000:456). Therefore, with an explicit Teotihuacán-derived imagery, Yax Pasah recalls not only the ancestral home of the founder, but also the social memory of the Copán people.

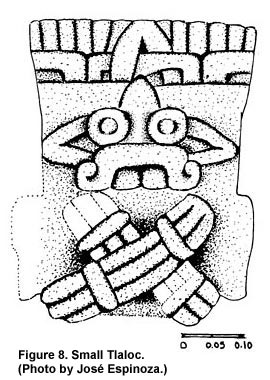

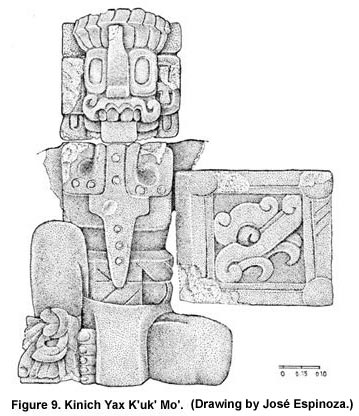

Another interesting motif carrying Tlaloc attributes is the so-called Tlaloc Block; this name refers to its form and style, which is found on one single block of tuff. In 1995, B. Fash and Taube, while working on the rearticulations for the exhibitions at the Sculpture Museum, found another motif that may be part of the Tlaloc Block. This season, I found a motif that is likely part of the same assemblage; it complements the lower part of the mosaic. Upon completion of its refitting process (Figure 8, shown above) the figure recalls the images that decorated the Temple 10L-33 at the residential royal complex 10L-2 or Cementerio (Andrews V and B. Fash 1992:70, fig. 7b; Schele 1992, fig. 8d). His face has rings around the eyes with rolling fangs on the sides framing two superior incisor teeth (primary Tlaloc attributes) and the Mexican year sign crowns his head–this is a secondary Tlaloc feature (Winning 1987:77). Two tied bundles compose the lower part of the body, as in a cross-legged position. This iconographic component recalls the founder glyph on top of Altar Q and other monuments where the founder is also mentioned. As a whole (0.40 width and 0.55 m high), the image is portrayed with his arms resting at his waist, in a cross-legged position and carrying the Mexican year symbol. The entire assemblage reminds one of the old fire god representations of Teotihuacán and the ancestors on the Structure 10L-29 of the residential royal complex at Copán (Cementerio); here they carry the kin, a sun symbol (Andrews V and B. Fash 1996:166). Nevertheless, this figure, as with other representations from the Structure 10L-33 at the Cementerio, becomes a variant of the founder’s motif (Andrews V and B. Fash 1992:70; Schele 1992: fig. 8d). I propose the hypothesis that this image is a representation (and evocation) of the founder KYKM. On the upper section of the first floor, Yax Pasah portrayed clear images of the founder KYKM (Figure 9). In an almost life-size form, he is featured in warrior costume and in a seated position, almost identical in form to the figure on Altar Q. The head features (goggled eyes, lolling tongue) evidently represent the apotheosis of KYKM as the Mexican Tlaloc god. He is also portrayed with Kan Cross ear spools, a typical Tlaloc attribute and a common motif at Copán. Although a throne has not yet been recovered, the founder is portrayed with his left leg crossed perpendicular to the right leg. As with the images on Altar Q and the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Copán, he is portrayed in a warrior costume, bearing on his left forearm a rectangular shield with the image of a serpent, probably a Teotihuacán war serpent. His skull-like head and rectangular ear flares resemble other Tlaloc sculpture heads recovered from Structure 16 (Taube 2000: figures 11a-d) and other Late Classic monuments at Copán (Baudez 1994: fig. 63 and 64; Taube 2000: figures 11e-f; [Figure 6]). Like the western Stair Block 1 of Structure 16, this figure’s head features a lolling tongue with perforator-like ending11 with circles that could represent drops of blood; on the sides of the mouth, large fangs roll up in a spiral form. Like most of Tlaloc representations in the Maya area, the head lacks a lower maw. KYKM position as a warrior is supported by other archaeological data. The interment of the Hunal Tomb surely contains the remains of the founder (Bell 2001; Sharer 2000:10). Bone analysis indicates a fracture on his right arm, convincing evidence for injuries suffered during battle (Buikstra et al. 1997; 2001). It seems likely that a Mexican year symbol–a Teotihuacán symbol associated with war in Maya art (Proskouriakoff 1973)–crowned his head. Yax Pasah appears to have repeated the theme of war depicted by his predecessor Smoke Shell on the Hieroglyphic Stairway (Stone 1996:207, 208; W. Fash 2000:145). Yax Pasah is the only ruler that constructed overt and explicit KYKM imagery on his monuments. I suggest that the figure of the founder and his probable veneration through accompanying rituals was a political symbol used by Yax Pasah to support his rulership and to perpetuate the dynastic succession, which unfortunately did not last much longer. As recent archaeological findings in hieroglyphic decipherment show, his power derived from the paramount political figure of Copán history. Yax Pasah also sought to reinforce his authority through symbolic cosmological terms. Of the image just described above (that of the founder), there were at least four figures around the first floor of the building, two on each of the north and south façades. These portraits are displayed on the façade of the building, I suggest, to mark the four directional points within a cosmological context. The cosmogram conveyed through these images is completed with a central or fifth figure. This figure, found in the middle of the building may be KYKM–with a pectoral the same as the one he bears on Altar Q. This figure, inside a serpent mouth, stood at the center of the world, unifying not only the four quarters, but joining sky, earth, and underworld. This scheme is a repetition of the cosmogram depicted with Tlaloc images in Teotihuacán derived style in the iconography of Escuintla in the Pacific Coast of Guatemala (Hellmuth 1975). The conception of the world in a quincunx form is a pan-Mesoamerican feature (Butterworth 1970; Carlson 1981:146-152). For the Maya, the universe was divided into four parts with a center or axis (Thompson 1961:225, 228; 1970:194-196; Schele and Mathews 1998:27). This quadripartite scheme is a pattern extended to Maya houses, temples, cornfields, community settlements, and larger socio-political spaces (Ashmore 1989:272; Bassie-Sweet 1991:172; Coe 1965:107-109; Girard 1949:893, 894, 897).

|

||

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||