| FAMSI © 2007: William R. Fowler |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The End of Pre-Columbian Pipil Civilization, Ciudad Vieja, El Salvador The Ceramics of Ciudad Vieja One of the most concrete manifestations of culture change at Ciudad Vieja can be found in the locally produced ceramic vessels, in particular, those used for serving and eating food. Barring the specific depredations experienced by those enslaved or otherwise oppressed in the villa of San Salvador, food consumption occurred several times every day, in every household in town, during the occupation of the site. The regularity of consumption means regular replacement of broken, or sometimes, out of fashion, serving vessels and implements. Furthermore, while eating can be a simple affair, or an intimate one, dining can also be an important social, political, or even ritual activity. The vast majority of pottery used at Ciudad Vieja was of local production by indigenous potters. Spanish potters had barely begun work in the American colonies during the occupation of the villa of San Salvador, at La Isabella in Hispaniola (Deagan and Cruxent 2002), and probably in México City after 1530 (Lister and Lister 1982), but these industries do not seem to have had much impact on Ciudad Vieja. Spanish pottery makes up only a small percentage of the Ciudad Vieja ceramic collection. Transport vessels, in the form of cheap amphora-like "olive jars" used for moving liquids or grains over land (Goggin 1960; Marken 1994), and majolica drug jars containing medicines (Lister and Lister 1987), are the most common of the imported ceramics. The olive jars provide the best artifact-based evidence for agreement with the historically-documented occupation and abandonment dates of the villa de San Salvador. The excavated examples all correspond to the Early Period of thin-walled spouts, with no examples of the Middle period thick "donut" necks (Deagan 1987, Goggin 1960). We have not recovered any Ming porcelain from Ciudad Vieja, which began to appear in Central America and New Spain after A.D. 1572. A small number of tin-glazed majolica serving vessels, escudilla bowls and brimmed plates, was imported from Seville (Deagan 1987; Goggin 1968), represented in the ceramic assemblage by a handful of sherds. The lack of Spanish utilitarian household ceramics, especially cooking vessels, is a pattern replicated throughout the colonies (McEwan 1992). A major factor for this pattern is most likely based on gender; that is, men made up the bulk of European immigrants to the Spanish colonies during the first decades of the Conquest. Indigenous women would have been the primary cooks of San Salvador, and not surprisingly, as is the case in other Spanish colonies, food preparation vessels show the greatest continuity from pre-Conquest times (Ewen 1991). The following analysis is composed of three parts: The first is a preliminary but comprehensive descriptive classification of the indigenous ceramics that make up the majority of artifacts recovered from Ciudad Vieja. In addition to being of interest in understanding the Villa de San Salvador and the beginnings of colonial society in Central America, this classification will be of interest to archaeologists studying Postclassic sites in the region. While analysis is still underway, relationships to previously published types are presented where possible. The second part is a short discussion of imported European ceramics found at Ciudad Vieja. The small quantity of olive jars and majolica are important for cross-dating, and for understanding some of the transformations in indigenous craft manufacture during the early sixteenth century. The third section is an overview and introduction to an analysis of one of the most intriguing elements of material culture at Ciudad Vieja; indigenously produced serving vessels that incorporate stylistically the form of imported European majolica plates. These colono ware vessels were given particular attention because of what they may reveal about the contact between Mesoamerican and European cultures. In addition to being valuable chronological markers in their own right, and a physical manifestation of cultural hybridization very early in the phenomenon of the Spanish Conquest, we have found that the hybrid plates of Ciudad Vieja also reflect a major element of the indigenous community of the villa of San Salvador. (See Figure 6.) A nested hierarchy of analyses were conducted during the study of the Ciudad Vieja ceramic collection. These include the following: Type Description – described below. This is the most basic analysis of the Ciudad Vieja collection. Preliminary group and type descriptions are included in this report, more detailed attribute analysis and tallies are in process. A preliminary estimate of roughly 10,000 sherds were analyzed in full for type description, with an additional estimated 15,000 sherds classed to type within the primary ceramic group. A separate database of handles, and another of tripod supports, classified by form and metric attributes, were created to aid in this analysis. Plate Data Base – Detailed analysis of sherds from 618 hybrid colonware plates produced by indigenous potters, but using European plate forms. Methods and results included in this report. Form and Function – Detailed analysis of rim form and other evidence for the use vessels. 1,900 rim sherds were classified by rim profile (at least 1,023 rim sherds were individually drawn by Card, the remainder were classified as sufficiently similar to those drawn), and additional metric measurements (orifice diameter, vessel wall thickness, vessel wall angle) and non-metric measurements (presence and type of handle, sooting or other evidence of use). Classification of these vessels into form categories and potential functional categories is underway. Correspondence analysis of presumed excavated activity areas using preliminary form categories has yielded some interesting results in comparison with other architectural and artifact evidence, but more work is needed. Preliminary Group and Type Descriptions Data Collection The following information was recorded for each sherd analyzed in full:

Fuller analysis, including at the level of variety and of the range of forms for each specific type and variety, is ongoing. All lots were initially screened through a plastic 1.5 cm mesh. All sherds smaller than 1.5 cm were tallied and weighed with no further analysis. All diagnostic sherds of the primary Alvarado group were analyzed in full (rims, handles, bases, tapas, sherds with paint or other form of decoration, slips of a color other than the paste body). In addition, all sherds that could be identified as being from plates were analyzed. All potsherds that were picked out during sampling as being of a group other than Alvarado were also analyzed. Of the remaining nondiagnostic sherds (non-decorated Alvarado group body sherds), 15% (sampled for each lot, rounding up) were sampled for full analysis. In the case of Figueroa type sherds, these were sampled separately, so as to maintain a record of the full count of Figueroa sherds versus normal Alvarado sherds. In practice this strategy resulted in full analysis of roughly 40% (by weight) of Alvarado group sherds, and roughly 50% of all sherds (by weight). Since all non-analyzed sherds are non-diagnostic body sherds, we feel confident that this sample is sufficient for understanding the Ciudad Vieja collection. Late Postclassic/Conquest Component Alvarado Group: The Alvarado group encompasses the most commonly encountered ceramic vessel artifacts at Ciudad Vieja, and may only be eclipsed in all artifact categories by ceramic roof tile fragments associated with structures built in Spanish style. Artifact tallying is still underway, but a preliminary overview of the collection suggests that 80+% of all ceramic vessel artifacts recovered from Ciudad Vieja belong to the Alvarado group. The following types are part of the Alvarado Group:

Paste (for all Alvarado with stated exceptions): General Description: Alvarado paste can be divided along two axes: inclusion density (coarseness) and color. Inclusions: A wide variety of inclusions are found in Alvarado sherds, including small fragments of obsidian, quartz, grog, and small red ferric inclusions, and small unidentified black minerals. However, the primary inclusion is white volcanic pumice. Under 10x–20x magnification, inclusion particles were recorded in the size classes of Medium Sand (2.0–0.43 mm) and Fine Sand (0.43–0.08 mm) in the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS). The density of particles in each of these size ranges was then estimated through visual comparison with a density chart. Alvarado paste was broken into two basic groupings (coarse & fine) based on the density of medium sand-sized particles. Sherds presenting an estimated 3% or less of medium sand particles were classed as Fine Alvarado, while all other sherds were classed as Coarse Alvarado. Color: Alvarado paste can range from brown to nearly cream/white, but the bulk ranges from a light brown to reddish yellow, and would be considered "buff." Observation of partial vessels and large sherds shows that Alvarado paste color can change quite dramatically within a single vessel, especially in terms of lighter and darker shades, but also in hue. The basic color difference that was used in classing Alvarado paste was the presence of a reddish tinge to the paste. Alvarado sherds that did not present a significant reddish or yellowish tinge were classified as Pale Alvarado. Such sherds range from a very light to a medium brown. Sherds that did present a yellowish or reddish tinge were classed as Orange Alvarado. In some cases, orange is a proper description for these sherds, but in many cases a yellowish brown is more accurate. While it is possible that in some cases, vessel integrity will be violated by the differentiation of orange and pale Alvarado, some vessels show that while chroma and value may change, basic hue is somewhat more resistant. This is why subtle shifts in hue/chroma were chosen over more obvious differences in value. However, due to these uncertainties, differentiation based on color is subordinate to differentiation based on inclusion particle size and density. Most common colors (Munsell):

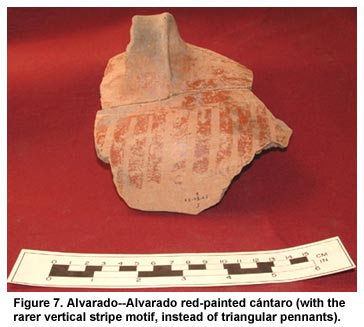

Types Alvarado–Alvarado General attributes: Self-slipped buff to orange vessels. Wide variety of forms. Red painted geometric decorations on water bottles (cántaros) and serving vessels (mostly hybrid-form plates, some bowls). Paste: See above. Surface treatment: Typically smoothed, burnished, or polished. Interior of water bottles are distinctively scraped. Most examples are probably self-slipped. Decoration: Some cántaros (specifically, pale/buff vessels with recurve bulbous necks are decorated; a separate class of typically orange-paste "trumpet" outcurving necked cántaros are undecorated) and serving vessels were decorated with red (10R 3/6, 4/4) painted geometric designs. Plates and bowls most commonly have parallel lines arranged perpendicular to the rim of the vessel (vertical in bowls, pointing inward in horizontal plates). More varied designs are found in small numbers. Most bowls have a solid red rim band. Cántaros are divided into three zones for the purposes of decoration. The neck (if bulbous, see below) may have a diagonal set of zigzag lines surrounded by straight lines perpendicular to the zigzag. The shoulder of the vessel is covered with a field of red paint intersected by non-painted "channels" of vessel surface color that form angular abstract or scroll motifs. The lower body of the cántaro below the shoulder is mostly unpainted, but includes vertically descending red painted wide stripes or pennants. This decoration scheme is very similar to that of Early Postclassic Nunuapa Red-Painted–Nunuapa cántaros of Chalchuapa (Sharer 1978:60, Figure 30e:1-3).

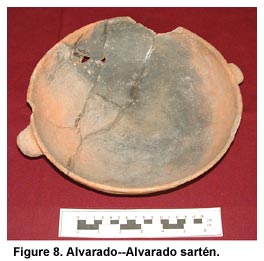

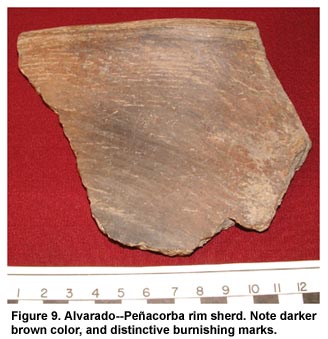

Forms: Wide variety of storage and/or cooking (incurving, straight-walled, and short-necked jars; comal griddles; shallow sartén frying pans), transport (cántaros), and serving vessels (hybrid plates, bowls). Cántaros have vertical strap handles, but strap handles (both vertical and horizontal) are used on a wide variety of forms. One form is unique to Alvarado–Alvarado, the zoomorphic support tripod bowl. Discussion Based on Amaroli (1992) as well as observation and study of pottery from the Río Ceniza valley, in the Izalco region (Kathryn E. Sampeck, personal communication, 2002), both Amaroli's Cuscatlán and Teshcal groups seem to bear a similarity to the Alvarado group. Amaroli (1992:12-13) described the paste of the Cuscatlán group as, "café rojizo a café amarillento claro ('bayo'), sin núcleos, con particulas entre rojizas a negras, redondeadas y angulares, de 1 mm o menos. Densa pero no excepcionalmente dura." Amaroli's Cuscatlán group is found in the same area of central El Salvador that includes Ciudad Vieja, and other elements of the group (form, decoration) are in agreement. While the medium sand classification used in the description above ranges to 2 mm, the bulk of particles in this class in the observed ceramics are closer to 1 mm in size. Alvarado group ceramics can present lighter or less oxidized cores, but this attribute does not occur on a regular enough basis to be diagnostic. However, Amaroli's description of the paste of Teshcal group ceramics, found primarily in the Izalcos region, is difficult to segregate from that given for Cuscatlán. Teshcal paste is "café rojizo medio hasta claro, con partículas heterogéneas oscuras, redondeadas y angulares, de 1 mm o menos" (Amaroli 1992:15). From this description, it would appear that Teshcal ceramics are perhaps slightly less yellowish (though still reddish) than Cuscatlán ceramics. Both are generally burnished but not slipped. Instead, the primary difference seems to be one of form (Teshcal vessels are typically bowl-shaped) and decoration (durability of paint, design motifs). Observation and study of sherds classified as Teshcal by Sampeck in the Río Ceniza valley (Kathryn E. Sampeck, personal communication, 2002) suggests that those materials show similarities to Alvarado–Alvarado. It therefore seems unfeasible, at this point, to make a differentiation. Overall, all of these types are sixteenth-century variants of a general red on natural buff tradition in Postclassic El Salvador that includes Nunuapa Red Painted from Sharer's (1978) Early Postclassic Matzin component and Late Postclassic Marihua Red on Buff (Haberland 1964). Alvarado–Castellon Distinguishing characteristics: Similar to Alvarado–Alvarado, but show evidence of being solidly slipped red. Emphasis on hybrid plate forms. Alvarado–Figueroa Distinguishing characteristics: Harder variety of Alvarado group paste. Paste: Upon visual inspection, appears identical to normal Alvarado ware paste. However, the paste is harder than that of the larger Alvarado group, and requires more force to break. When broken, does not typically fragment or crumble, instead produces clean breaks and "sharp" edges. Sherds will clink or ring when tapped with or against a hard surface. Form: Wide variety, like Alvarado. Body is slightly thinner than that of typical Alvarado vessels. Surface: Polished or burnished. May be particularly lustrous but may also be relatively matte. Burnishing can in some cases be sloppy, or slightly linear, but Figueroa is not characterized by linear burnishing. Decoration: Similar to that of Alvarado–Alvarado, though less commonly decorated. Discussion: The hardness may be due to particularly intense polishing or burnishing (but see Figueroa), or it may be due to higher firing temperatures. Found at a few other locations on site, but the bulk of the type was found in and around Structure 3D2. The occurrence of an iron forge within this structure has suggested the possibility that Figueroa vessels may result from firing at higher temperatures within the forge, but this suggestion requires additional excavation elsewhere on site, and possibly physical testing, for confirmation. Alvarado–Peñacorba Distinguishing characteristics: Hard paste like Figueroa. Linear burnishing. Darker color. Emphasis on utilitarian forms. Paste: Extremely hard, even harder than Figueroa. Unlike Figueroa, Peñacorba differs from the standard Alvarado population by tending more to the brown and black, either through reduction firing or through use. Rings when struck, does not crumble, breaks with clean and sharp edges. Form: Includes most forms in the Alvarado inventory, but with an emphasis on utilitarian cooking wares. Whether this is a primary characteristic of the type, or if this reflects the activities of the activity area within which the type is found (see Discussion), or both, is uncertain. Surface: Some surfaces can be highly polished, but the primary distinguishing characteristic of Peñacorba is intensely burnished surfaces, usually linear burnished (with some gaps left between burnishing facets). Decoration: Some serving vessels are decorated, but the emphasis on utilitarian vessels leaves most Peñacorba vessels plain. Discussion: While firing may play a role in the hardness of Peñacorba paste, the intense burnishing must also play a role. With perhaps one or two exceptions (individual sherds), this type was found exclusively in Structure 6F4. Excavation of other middens at Ciudad Vieja, have turned up cooking vessels in large quantities, but not the Peñacorba type. This suggests that, while there may be a functional element to the presence of Peñacorba as a primarily utilitarian cooking ware, the exclusive distribution of the type at Structure 6F4 may reflect either a chronological difference, and/or evidence for localized production of these vessels for the kitchen at Structure 6F4, and/or evidence for a different distribution pathway for ceramic vessels to Structure 6F4 than the other excavated areas of the site. The form of a number of Peñacorba ollas, and the linear burnishing, show strong ties to, or possibly a local variant of, the protohistoric Joateca type from Chalchuapa (Sharer 1978: 64-65).

Alvarado–Oliveros Distinguishing characteristics: Crumbly paste, often brown. Low quantity of inclusions, but unlike well-sorted Fine texture vessels, the lack of inclusions makes these crudely formed vessels friable. Utilitarian vessels, rarely decorated. Type classification still in process. Alvarado–Sandy Distinguishing characteristics: Perhaps a variant of Alvarado–Alvarado. Higher quartz sand/grit content. Surfaces erode more easily, and when handled leave substantial sand dust. Some examples of large compound sartén cooking pans have a thin red or orange wash or slip on vessel exterior. Otherwise, similar to Alvarado–Alvarado Coarse. Possible Types Within the Alvarado Group The following three types may be part of the Alvarado group, but some paste differences led to initial separate classification. Salvago Distinguishing characteristics: Similar to Alvarado–Figueroa–Coarse, typically orange in color. However, Salvago has only low quantities of medium-sized white pumice fragments, a major element of the standard Alvarado temper mix. A large number are from cántaro vessels, but the paste can occur in other forms.

Bonifacio Distinguishing characteristics: Likely part of Alvarado–Alvarado, some examples have Salvago-style paste, leading to initial separate classification. Otherwise, is a variant of the Alvarado–Alvarado painted cántaro described above. Decorated with a trichrome pattern large red fields on cántaros. In between these painted fields are channels of the underlying pale to orange paste color. Within these channels are medium to thin painted black lines that run parallel to the edge of the channel/red fields. It appears to be analogous to Early Postclassic Chamula Polychrome from Chalchuapa (Sharer 1978:60).

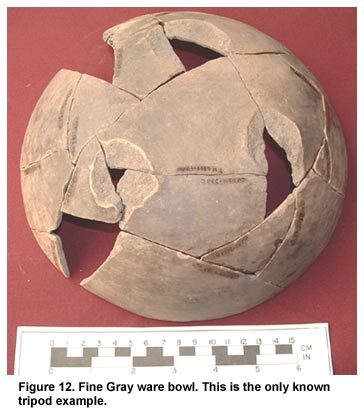

Holguín Distinguishing characteristics: Brown-black reduced fine paste, though not friable like Alvarado–Oliveros. Utilitarian "sack" vessels, tab or small horizontal strap handles. Paste: Finely tempered, but since most examples are burnt or reduced to a dark brown or black, classification is somewhat difficult. Lacks the medium white pumice of most Alvarado. Not friable like Alvarado–Oliveros. Color: Typically dark brown or black on exterior (7.5YR 3/2, 5YR 4/2, 5YR 3/1). Interior can be a well smoothed pale or brown (7.5YR 4/2, 5YR 4/2). Decoration: None Surface treatment: Interior generally smoothed or lightly polished. Exterior usually burnished below shoulder. Forms: Utilitarian open-mouthed cooking vessels, often with relatively straight walls ("sack" vessels). Small tab or horizontal strap handles are located below rim. Discussion: Very similar to Pantaleón vessels at later sixteenth-century Caluco in western El Salvador (Verhagen 1997; Kathryn E. Sampeck, personal communication, 2002). Non-Alvarado Groups Fine Gray Ware Distinguishing characteristics: Extremely fine gray to brown paste. Highly polished and lustrous surfaces. Incurving bowls, potentially with tripod supports. Paste: An extremely fine gray, dark gray, or brown. Temper is completely fine in size, and in some cases virtually non-existent. Cores can take up much of clay body. Form: Incurving or slightly incurving bowls are the only form for this group. No handles, tabs, or lugs. The most complete example has scars from tripod supports, but there is no evidence as to the size or form of the supports. Surface treatment: Extremely well polished interior and exterior, with a slightly streaky quality when it comes to color variation in the vessel. Some examples have scorching or fire-clouding on the bottom of the interior and exterior of the vessel, but whether this is due to firing or use over a fire is unknown. Decoration: None. Discussion: One of the major non-Alvarado groups at Ciudad Vieja. Present in low but persistent quantities in most excavations. William Fowler and Howard Earnest (personal communication) suggest potential match to the gray bowl tradition of Oaxaca (Fowler) or possibly Puebla (Earnest). There does seem to be some general similarity in regards to form for Late Postclassic Bowls (see Markens 2004 for Chila phase grayware tripod bowls), but personal communication with archaeologists working in Oaxaca (Joyce Marcus, personal communication, 2003) has contradicted this. At this time, potential connections to other regions of Mesoamerica must wait for further analysis. If the Fine Gray bowls are eventually tied to another region, one possible explanation for their presence may come from the presence of Mexican auxiliary troops at Ciudad Vieja. All of the vessels are medium sized bowls, somewhat incurving in most cases. A few examples suggest possible use over a fire, but the bowls would also be quite suited to serving and consumption of food. Perhaps these bowls were a form of mess kit for warriors on the move in a long-distance campaign, serving as 2-in-1 cooking and dining bowls for Mexican men cooking for themselves and with no desire to carry a larger array of food preparation vessels.

Usagre Distinguishing characteristics: Thick (around 1 cm) vessel walls. Gray to slightly yellowish paste (not the same as Fine Gray bowls). Primarily quartz and pumice temper. Thick loop handles. Utilitarian jars or bottles. Thick, dark gray cores. Paste: The paste itself seems finer and denser than that of Alvarado, also more easily eroded. Tempering can be fine or coarse, but temper is primarily quartz and pumice, and not the more varied mix of the Alvarado group. Vessel walls are thick, typically around 0.75 cm, but ranging from 0.57–1.78 cm (10 examples). Roughly one-quarter (11 of 45 examples), has a thick dark gray core (10YR 4/1, 5/1). Vessel color is generally a light gray to dirty white, with some hint of yellow in a few cases (10YR 5/4, 6/3, 6/4, 6/6, 7/2, 7/3, 7/4, 7/6, 8/1, 8/2, 8/3, 8/8). Form: Only one rim (Rim 1340) was recovered for this type, an open, nearly flat vessel with a tapering rim (Rim Form 722) with an orifice diameter of 28 cm. However, the recovered body sherds indicate that most Usagre vessels had globular incurving bodies. Five handles were recovered; two loop handles, and three strap handles. While no neck fragments have been recovered, one-quarter (11 of 45 examples) are scraped on the interior, a feature associated with cántaro water bottles at Ciudad Vieja, and an additional two examples have rough non-smoothed interiors. Surface treatment: Exterior generally polished (21 examples), smoothed (12 examples), or burnished (6 examples). Interior surfaces roughly split between scraped (11 examples), polished (11 examples), and smoothed (8 examples). Decoration: One vessel had a light orange wash applied to the interior and exterior of the vessel, and another had a remnant of red paint on the exterior, but otherwise, the surfaces are not slipped or painted. Discussion: Preliminary analysis suggests a possible link to one of Sharer's (1978:75) special minority types, Crude-unslipped, from the Late Postclassic to Protohistoric Ahal component of Chalchuapa.

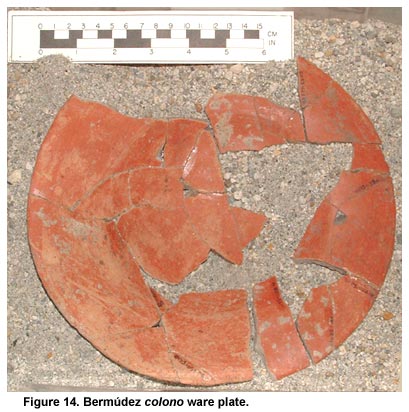

Bermúdez: Distinguishing characteristics: Fine soft orange paste. Typically completely red slipped. Paste: Finely tempered, lacking the medium sized tuff/pumice inclusions of the Alvarado Group. Paste is orange, very soft and easily eroded. In at least one case, firing core occupied nearly entire body, with a dark gray in one half of vessel, while in another paste is strongly orange. Form: Primarily colono plates (Italianate, as well as two of the Morisco plates). Two examples of scalloped rim bowl, also influenced by European ceramics and glassware. Pedestal foot (possibly for cup, but may also be in imitation of footed plates and dishes of Italianate Majolica tradition). Exterior knob appliqué. Bowl. Handled vessel, likely bottle or necked jar (forms H2, H13 vertical). Surface treatment: Usually covered interior and exterior with a thick, soft, red slip. The slip may be burnished or especially polished, but in other cases, is simply applied and not further treated. In some cases the exterior is not slipped, though after polishing, the strong orange color of the paste, after polishing or burnishing, may be difficult to distinguish upon initial observation from the interior slip. Decoration: Typically undecorated red slip. One example with what may be a resist pattern of lines perpendicular to the interior brim of colono plate. One example with two horizontal black lines.

Discussion: Besides the Fine Gray Bowls, this is the only other major non-Alvarado ware at Ciudad Vieja. Part of the Postclassic red bowl tradition in El Salvador (Cihuatán, Izalco). Appears related to the Postclassic and possibly protohistoric Guajoyo Red-brown from Chalchuapa (Sharer 1978:62-63) and García Red from Guazapa-phase Early Postclassic central El Salvador (Fowler 1981:163-178). Classified by Sampeck (personal communication, 2002) as Teofilo (Verhagen 1997), but there are some significant paste and slip differences. Scalloped rim bowls and presence at Caluco raise the possibility that this may be a somewhat later group than Alvarado, but it is equally plausible that both Alvarado and Bermúdez date to the entire Ciudad Vieja occupation, and Bermúdez simply thrives somewhat more either in the west, or later in time.

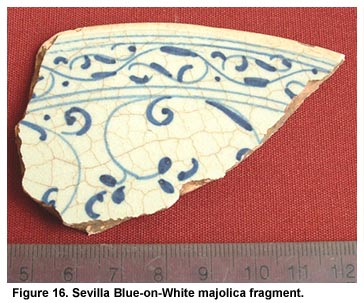

Catalina Red-on-White: Distinguishing characteristics: Brick Red Paste. White, cream, or light tan slipped interior, tan slipped exterior. Broad red rim band. Geometric red designs. Paste: Typically, though not always, brick red paste (exception is a light brown), relatively fine. Form: Open bowls or deep dishes. Surface treatment: Interior slipped cream/white or light tan. Exterior slipped either cream/white, or tan. The white/cream slip may be an earlier feature, becoming less common through time, especially during and after the Conquest. Usually polished on both surfaces, or well-smoothed. Decoration: Broad, clean-edge, red band on interior and exterior of rim. From Ciudad Vieja materials, decoration is difficult to describe beyond being red geometric. However, comparison with Sampeck's materials from western El Salvador show more detailed designs, including step-frets and scrolls, than those of the Alvarado group. Discussion: In Kathryn Sampeck's work in the Izalcos region (type defined as part of this work, Sampeck, personal communication, 2002), it seems that Catalina is the precursor of the Protohistoric Teshcal group (Amaroli 1992). Given the obvious similarities between Teshcal, the Cuscatlán group as defined by Amaroli (1992), and the Alvarado group, Catalina is presumably ancestrally related to all of these Postclassic (Haberland 1964) and Protohistoric red-on-buff traditions. However, the scarce two sherds of Catalina Red-on-White found at Ciudad Vieja suggest it may be an isolated trade/carry ware. In addition to the primary Late Postclassic/Contact component, a smattering of sherds of Early Postclassic date (Cobos 1994:74-85) have been found in isolated contexts, including white-slipped Nicoya Polychromes, Las Lajas, and Tohil Plumbate, all of which are part of the Early Postclassic Guazapa ceramic complex defined by Fowler (1981:117-269) at Cihuatán, El Salvador. However, to date, no actual deposits dating to this period have been found at Ciudad Vieja. Late or Postcolonial Component Crudely formed massive "comma"-rimmed comales and sugar straining vessels are found primarily on the surface at Ciudad Vieja, though occasionally in excavated contexts. Further classification of these sherds is ongoing, but they are currently classified as a 19th–20th century type called Telesforo in western El Salvador (Sampeck, personal communication, 2002). The thick walls of these vessels (typically over 1 cm, double or more the average thickness of protohistoric vessel walls) make for relatively easy identification. Type Classification: Discussion Overall, the bulk of Ciudad Vieja pottery is not a major departure from that of the Early or Late Postclassic, with ties to groups defined at Chalchuapa, Cihuatán, and other locations in central and western El Salvador. As would be expected in a Spanish colonial town, ritual forms such as censers have all but disappeared. Gone too are any influences from the pan-Mesoamerican Mixteca Puebla art style that in some sense defines the Postclassic period as an archaeological horizon. Artwork depicting animal or human figures disappears, with the possible exception of abstractly zoomorphic supports for tripod bowls. Molcajetes have also vanished from the kitchen inventory, a puzzling development given the otherwise strong indigenous influence in domestic culture. Somewhat more surprising is the importance of indigenous serving and other decorated wares in all parts of Ciudad Vieja. As noted to a lesser extent in sixteenth-century México City (Rodríguez-Alegría, Neff, and Glascock 2003), indigenous ceramics retained their importance at Ciudad Vieja, in what was considered a Spanish conquest center. This point is examined in further detail below in the section on hybrid colono ware plates. Spanish Pottery at Ciudad Vieja Five hundred sixty fragments (adjusted to 475 possibly from individual vessels) of Spanish Olive Jars have been recovered from Ciudad Vieja. Though complete ceramic tallies are not finished, it is doubtful that Olive Jars make up more than 2% of the entire Ciudad Vieja ceramic assemblage, an extremely low quantity for a typical Spanish colonial site. Olive jars are considered a ubiquitous feature of Spanish colonial sites, discarded after the transport of liquids or granular solids from ship landings. With one exception, all Olive Jar rims at Ciudad Vieja belong to the Goggin's (1960) early style (see also Marken 1994: Fig. 4.1), replaced by doughnut-necked middle-style jars in the Spanish colonies by 1580, though perhaps as early as the 1560s (James 1988:59). The one exception may be a very late Olive Jar, perhaps dating to the nineteenth-century occupation of Ciudad Vieja associated with Hacienda La Bermuda. Olive Jar vessel walls at Ciudad Vieja average 0.65 cm in diameter, just under and in agreement with the rough 0.7 cm thickness of Goggin's (1960:Table 8) early-style jars, and in contrast with the 1.0–1.2 cm thick middle-style jars. Unfortunately, while large jar fragments were recovered, none are very informative regarding form. No Olive Jar handles have been recovered from Ciudad Vieja, and only one possible handle scar on a body sherd (and not from controlled excavation context). Goggin (1960) emphasized handles as distinctive of early-style jars, while Marken (1994) did not. Close to half of all Olive Jar fragments were recovered from Structure 3D2, a possible marketplace located on the south edge of the main plaza, representing approximately 4% (by weight) of the total ceramic assemblage at that locus. Quantities are substantially smaller at other excavated contexts. This suggests that Olive Jars may have been discarded in some quantities near central markets or stores, but were not used for substantial transport or storage within the rest of the site. Chronologically, the Olive Jar specimens place the main occupation of Ciudad Vieja in the early to mid-sixteenth century. Twenty-three majolica fragments were recovered from Ciudad Vieja. The influence of majolica on indigenous pottery traditions is detailed in the section on hybrid plates. However, the actual quantity of majolica is very small. Five fragments of Caparra Blue, a sixteenth-century type used for medicine jars, were found at Ciudad Vieja (Deagan 1987:62-63; Goggin 1968:134-135). Also dating to early during the colonial period is the small tab handle found on a Columbia Plain escudilla (Goggin 1968:122-123), one of nine Columbia Plain fragments. (See Figure 15.) The other significant identified type of majolica at Ciudad Vieja is Sevilla Blue-on-White, present as two fragments of plates. As discussed in the section on hybrid plates, this type is generally associated with the later sixteenth-century, but is found in México City as early as 1530 (Lister and Lister 1982).

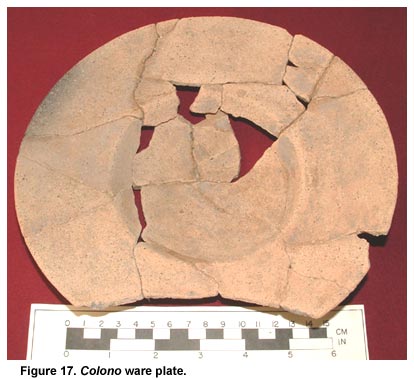

Locally Produced Hybrid Plates: An In-Depth Analysis of Ciudad Vieja Colono Ware The Spanish vecinos of San Salvador adopted indigenous ceramics into their lives with little trouble. Pottery with clear ties to the ceramic traditions of the pre-Hispanic Postclassic period dominates all archaeological contexts at Ciudad Vieja. But in the case of serving vessels, we also see the influence of the new colonists. The primary type of serving vessel found at Ciudad Vieja is a buff- to orange-colored, low-fired, unglazed, brimmed plate, often painted in red with motifs that harken back into the Postclassic period. This form closely copies that of imported majolica plates, while preserving the technological and other aesthetic elements of pre-Columbian Pipil ceramic traditions. This phenomenon of stylistic adoption of European ceramic traits by indigenous American potters has been recorded at other colonial sites in the western hemisphere. Generally dubbed colono ware, the most common hypothesis concerning these vessels is that they are an indigenous response to scarcity of imported pottery desired by European settlers (Vernon 1988). A less visible and more recent approach has suggested that colono vessels are indicative in some way of indigenous acculturation into a European-dominated colonial society.

Traditionally Mesoamerican women were the primary creators of pottery vessels until the adoption of the pottery wheel and other European techniques (Reina and Hill 1978). We know that at least some indigenous women moved to San Salvador from elsewhere in Mesoamerica, as part of families including Spanish men. It is conceivable that some of these women may have been the creators of hybrid brimmed plates. However, in addition to the basic assumption that most migrants to Ciudad Vieja were male auxiliary troops, and that many of the women living in San Salvador were local Pipils, the most common decorative motif (see Figure 18) painted on these hybrid plates, is similar to designs painted on Postclassic serving bowls in central and western El Salvador (Verhagen 1997:Figure 7.1). These groups of parallel lines, connected by a perpendicular line, are found on Catalina Red-on-White bowls found in the Izalcos region of western El Salvador (one example has been recovered from Ciudad Vieja), and a similar pattern of vertical stripes is painted on the inside of a number of simple bowls found at Ciudad Vieja. This would indicate that hybrid brimmed plates were classified as "serving bowls" by the first generation of colonial Pipil potters. This should come as no surprise, as these vessels typically outnumber simple bowls by a factor of 2:1 or 3:1 in nearly all excavated contexts at Ciudad Vieja, and are found associated with every excavated structure. Structure 3D1, located near the center of San Salvador, and remarkable for boasting two sets of floor tiles of different sizes, and a high incidence of imported Spanish pottery (including a large number of olive jar fragments, a fragment of Columbia Plain majolica, and a Caparra Blue majolica drug jar), has the highest percentage of brimmed plates associated with it, making up 29% of all vessels with an identifiable form. The second-highest percentage of hybrid brimmed plates (23%) comes from Structure 2F1, the best candidate at Ciudad Vieja for an indigenous household, located on the outskirts of town, with no Spanish architecture or ceramics, minimal iron artifacts, and strong evidence for textile production with spindle whorls (almost certainly undertaken by a Mesoamerican woman). Only in Structures 6F1 and 5E2 do serving-ware bowls outnumber hybrid plates. On average, they make up roughly 17% of all ceramic vessels in a given assemblage.

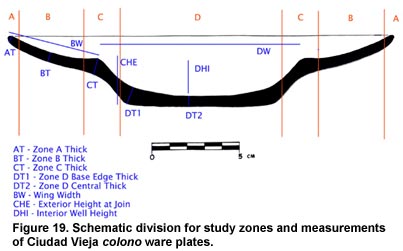

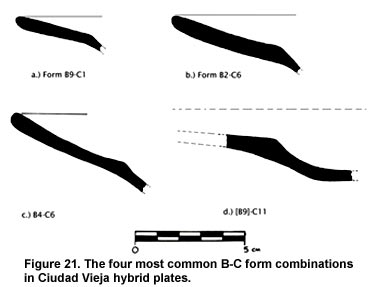

The bulk of ceramics at Ciudad Vieja belong to the Alvarado group and the Bermúdez groups (while Bermúdez plates are only a small portion of the entire plate population, plates are a large percentage of Bermúdez vessels) described above. While clearly related to the unpublished protohistoric Cuscatlán and Teshcal ceramic groups designated by Paul Amaroli (1992), the Ciudad Vieja ceramic assemblage provides a larger breadth of forms, especially hybrid brimmed plate serving vessels that are reported neither by Amaroli nor others studying the Protohistoric-Colonial period in El Salvador. Alvarado ceramics appear to also be related to Haberland's (1964) Postclassic Marihua Red-on-Buff, although Marihua painted lines are much broader and sloppier than those on Alvarado ceramics. In addition, 17 hybrid plate fragments (2.8% of all plates) belong to the red-slipped, fine orange-paste Bermúdez group. A total of 618 fragmented plates were classified in more detail than standard type classification, in particular through the use of four distinct zones comprising the body of the plate. For each of these zones, form, thickness, and any painted designs were recorded. In addition, orifice diameter, rim width, well diameter, and well depth were recorded when possible. Zone A consists of the lip/rim of the vessel. 393 examples could be classified by form in Zone A (64% of all plates). Form, thickness, and painted/slipped design motif were recorded for Zone A. Form was classified into one of 22 different categories by profile (A1–A24). Zone B consists of the area of a plate between the rim (excluding the lip as part of Zone A) and the arista (the "corner" where the wing meets the well, Lister and Lister 1975:18). In other words, Zone B is the brim (also known as the wing) of a brimmed plate. Form was classified into one of 13 (B1–B13) profile categories. Brim form could be classified for 482 plates (78% of all plates), making it the most commonly identified plate section. Zone C consists of the small, somewhat vertical, zone between the arista and the base of the plate. Zone C could be classified in 247 cases (40% of all plates), using 19 form categories (C1–C19). Two additional measurements were made here. The first is of the exterior height from the interior point of the arista to the bottom of the plate base (labeled CHE in Figure 19, shown below). The second measurement taken in this Zone was the horizontal diameter of the plate well. In most cases, this was estimated using the same orifice diameter charts used to determine vessel orifice diameter. Zone D consists of the base of the vessel. Basal morphology could be determined for only 93 of 618 plates (15%). Plate bases were classified into only nine (D1–D9) form categories. Well depth was recorded here (the vertical distance between the top of the Zone C join and the interior of the base, labeled DHI in Figure 19). The variables of type classification, surface treatment, and weight, applied to all ceramic sherds studied in the Ciudad Vieja collection, were recorded for each case.

The obvious defining characteristic of hybrid Alvarado group plates is form. While shallow platters and bowls, and some brimmed tripod vessels were produced in Mesoamerica prior to European contact, the brimmed plate does not seem to have an indigenous antecedent. The closest antecedents to the Alvarado plate form are Spanish and Italian majolica, tin-glazed serving vessels. Christian European potters began to appropriate this technique from Muslim potters in the thirteenth century, who themselves were copying Chinese porcelain (Carnegy 1993:12; Lister and Lister 1987; Poole 1997). (See Figure 20.) The Pipil potters who made the hybrid plates were very familiar with the original subject matter. Detailed analysis of vessel form by section, in comparison with published information on Spanish and Italian sixteenth-century majolica, reveals that the indigenous potters who made Alvarado plates had a keen eye for variation within European ceramic forms. Morisco-tradition majolica such as Columbia Plain is often the most commonly found majolica at sixteenth century Spanish colonial sites, but its form is poorly represented in the Alvarado hybrid plates. Five of the hybrid plates (0.8% of the total collection) have the distinctive thicker body, curved form, and low-ridge-like break between the "wing" and the "well" of the plate. These examples do not have the geometric designs common to Alvarado group vessels, and are instead red-slipped in part or whole. Two of the five are Bermúdez group ceramics, one of which has a mildly scalloped rim. Several small majolica fragments of the most common morisco type, Columbia Plain, have been identified at Ciudad Vieja. Instead, the vast majority of plates are the thinner walled, brimmed plates of the Italian tradition. Italian potters and technology began arriving in Seville in the sixteenth century, and by the middle of the century, Italian-style plates were an important product of Andalusia (Pleguezuelo and La Fuente 1995:237-240). Spanish-produced Sevillian ware plates, in the Italianate tradition, are uncommon in the Americas during the historically recorded occupation of Ciudad Vieja, but are present by roughly 1530, particularly in México City (Deagan 1987; Lister and Lister 1982).

An analysis of the Ciudad Vieja hybrid plates (Card 2005), in comparison with sixteenth century European majolica, shows very close similarities in form to Italian majolica contemporary with the historically documented occupation of Ciudad Vieja (Lessmann 1979; Watson 1986). Several of these forms are characterized by, in part, a horizontal flat brim. While no Italian majolica has been found at Ciudad Vieja, we have found two pieces of Italianate-style Spanish majolica, Sevilla Blue on White. It appears certain that the indigenous potters who produced the hybrid vessels were handling original majolica plates imported from Europe. Furthermore, while Morisco majolica is somewhat more common than Italianate majolica at Ciudad Vieja, over 95% of the hybrid plates have the newer and more stylish Italianate forms. Italianate, and not Morisco, forms also dominate the production of Spanish majolica potters in México City starting during the later part of the occupation of Ciudad Vieja (Lister and Lister 1982), though it should be noted we have no evidence for Mexican majolica at Ciudad Vieja. Alvarado Group hybrid plates are either plain or decorated with painted red geometric designs on orange to buff paste or orange to buff-self-slipped surfaces. Bermúdez group hybrid plates are by definition red slipped, and are mostly monochromatic (though one example was decorated with a two-tone "diagonal pi" motif). The most important zone for painted decoration on hybrid plates is the wide brim. The four most common decoration motifs on the brim include:

Such decoration links the hybrid plates not only to contemporary painted bowls and cántaros in the Ciudad Vieja assemblage, but to a deeper tradition represented in Postclassic El Salvador by Marihua Red on Buff, and possibly to the Pipil migrations from México (Fowler 1989:32-49). There was no attempt to adopt European painted designs or technologies, only form. Technologically, the Alvarado group hybrid plates are purely indigenous. There is no evidence for the use of the potter's wheel. None of the Alvarado group hybrid plates were glazed. The indigenous surface treatment techniques used to construct colono plates included: smoothing, burnishing, and linear burnishing (burnishing that leaves non-burnished 'streaks' between burnish facets or marks). As mentioned above in the discussion of form, the brim is the most sensitive and useful variable for classifying hybrid plates. The table below displays the relationship between brim form and interior surface treatment. Interior surfaces are roughly divided between non-lustrous smooth, and lustrous polished, with a few burnished examples. Flat-brimmed plates (B9 in Figure 21) were more likely than concave brimmed plates to be polished on the interior surface. This pattern is also observed for the exterior, but is less statistically reliable.

The isolation of flat-brimmed plates from the rest of the hybrid-plate population also extends to paste and temper sorting.

While in all cases the bulk of plates (like the bulk of Ciudad Vieja ceramics) are coarsely tempered, flat-brimmed plates (B9) were better sorted than plates with other forms. Conversely, steeply-angled concave brimmed plates were rarely finely sorted. This variation is even more statistically significant than surface treatment, with a p-value of 0.03. With the exception of morisco-style hybrid plates (all five of which are red-slipped), there are no significant surface color variations in regard to brim form, with roughly 75-85% of plates possessing a pale surface when one could be detected. Orange (10%) and brown surfaces (4%) seem to vary from pale surfaces due to firing variation or in some cases compacted and darker surfaces due to burnishing. Red slipped surfaces are found on 6.1% of the non-morisco hybrid plates. Implications for Indigenous Occupation of San Salvador and Sixteenth-Century Culture Change A common explanation for the adoption of European forms by indigenous potters in Spanish America is that of scarcity (Charlton and Fournier-Garcia 1993; Vernon 1988:79). Spanish settlers, hoping to replicate some elements of the home life they knew in Iberia, direct local potters to try as best they can to produce serving vessels reminiscent of hard-to-obtain European majolica. In some places, such as mission (Vernon 1988; Weisman 1992) or fort sites (Bense and Wilson 2003) in Spanish Florida, this explanation seems to work. At these sites, hybrid plates and other vessels are significantly more common in trash dumps and other contexts associated with Spanish architecture, than in nearby indigenous residential zones. However, this is not the case at Ciudad Vieja, where hybrid plates are encountered in large quantities across the site, in presumed Spanish and indigenous residential deposits. As we believe that a substantial number of inhabitants of Ciudad Vieja were indigenous to Mesoamerica, particularly those that resided in Structure 2F1, Ciudad Vieja does not support the hypothesis suggested for indigenously produced colono wares at other sites in the circum-Caribbean region, that such vessels were produced primarily for Spaniards hungry for familiar but unavailable material culture. Instead, while Spanish settlers may have been the initial impetus or "market" for this new form, it seems to have been embraced by the indigenous inhabitants of San Salvador. But only within San Salvador. Elsewhere in the former Pipil kingdoms of Izalco and Cuscatlán, brimmed hybrid vessels do not appear, even in assemblages where the rest of the ceramic inventory is clearly related to that of Ciudad Vieja (Amaroli 1992). Scalloped-lip red-slipped bowls, inspired by contemporary majolica or glass vessels, were used at late-sixteenth century Caluco (Verhagen 1997: Fig 7.17). Two examples of what may be similar bowls, both red slipped, were recovered from Ciudad Vieja. Verhagen also notes a deep, brimmed bowl (Fig 7.19). But brimmed hybrid plates are not present at later Caluco. The difference at Ciudad Vieja is the presence of large numbers of uprooted indigenous people living at a location that was not previously inhabited. Unlike México City, Santiago de los Caballeros, and other early Spanish colonial capitols including the first San Salvador of 1525 (Lardé y Larín 2000:85), Ciudad Vieja was not founded within the confines of an existing settlement (Barón Castro 1996:43). With the exception of new indios and mestizos born at Ciudad Vieja, all of the inhabitants would have moved there from their previous home. The Spanish and other European conquistadores were far from home, but so too were the Mesoamerican auxiliary troops and naborías that accompanied the Spanish colonists to Cuscatlán. The documentary record speaks of Spanish allies, native auxiliary troops, from México. Several hundreds to thousands of Tlaxcaltecs, Cholulans, Tetzcocans, and other "Mexicans" took part in the conquest of Guatemala, including what is now El Salvador (Barón Castro 1996:66; Escalante Arce 2001:20-21; Lardé y Larín 2000:53). While still within the greater culture area of Mesoamerica, Mexicans and Mayas would also have been far from home, foreigners to the Pipil and Europeans alike. Foreign Mesoamericans resident in San Salvador may have realized that in their culturally isolated situation, adoption of Spanish cultural elements may have been an important guarantor of continued recognition as indios amigos. Even those originating closer to San Salvador would have been away from home, as there was no settlement at Ciudad Vieja immediately before the arrival of the Spanish. Presumably some of the thousands of Indians held to encomienda requirements by the vecinos of San Salvador worked and lived, at least on a temporary basis, on-site. Spanish laws were designed to keep such absences to "reasonable" spans of time, such as four months (Sherman 1979:314). Other roles for indigenous people in San Salvador may have included as wives (San Salvador vecino Francisco Castellón married the Mixtec mestiza Catalina Gutiérrez in 1539 or 1540 [Lardé y Larín 2000:194-195, 260-261]), concubines (Sherman 1979:305-306), clients, itinerant laborers (some Indian laborers were paid to construct the new ciudad de San Salvador that replaced Ciudad Vieja [Sherman 1979:96]), apprentices, craftspeople, nurses (Sherman 1979:323), servants, or slaves (Lardé y Larín 2000:67; Sherman 1979:91, 196). Throughout the sixteenth-century, wage-laborers were isolated even further from their original communities by participation in Spanish-inspired religious fraternities (Rodríguez-Alegria 2002:125-126). Even if travel to nearby Pipil towns was frequent, Pipiles would have been to some degree strangers in a foreign-dominated colony, as well as increasingly in their home communities. Lastly, San Salvador was also a slaving colony (Sherman 1979:27). The vecinos of San Salvador, feeling that the Indians of their encomiendas were not sufficient, campaigned to the east of the Lempa with their indigenous auxiliaries, to acquire more slaves, specifically, Lencas. These lands and their inhabitants were soon redistributed after the founding of San Miguel in 1530, leading the San Salvadoreños to conquer into the mountains to the north, in the direction of Honduras-Higueras (Barón Castro 1996:135-136, 150, 165-166, 187). This situation was not unusual in the Spanish colonies. In Panama, only 27% of Indians counted in a 1550 census were locals (Cooke et al. 2003:22-23). Four-hundred slaves were liberated from San Salvador in 1548, only three years after the documented transfer away from Ciudad Vieja (Sherman 1979:73). The isolation from existing cultural and social networks may have increased the pressures of acculturation and syncretism on the non-Spanish inhabitants of Ciudad Vieja, particularly the non-Pipil. The cultural reinforcements built into a society's institutions that could act to slow acculturative processes (Rogers 1993), would have been largely absent inside of the Spanish colony of San Salvador. Hybridized vessels appear to be linked not so much to the adoption of European material culture, nor to daily interaction with Europeans, but to the dissolution of traditional indigenous society through the physical removal of people from existing pre-Hispanic settlements and resettlement in new towns and cities. In only two other cases, hybrid serving vessels, produced by indigenous potters, dominate serving vessels in a site's ceramic assemblage, making up close to 20% of the entire ceramic assemblage. One is Amelia Island, Florida, where missionized Guale Indians were resettled due to Franco-Spanish conflict (Saunders 2000:136-142). The other is Old Mobile, Alabama, where again due to Franco-Spanish conflict, missionized Apalachee Indians from Spanish Florida resettled in a French town (Cordell 2002; Silvia 2000). In both cases, indigenous potters had begun making colono wares, but in small quantities, prior to resettlement. Due to their discovery primarily in Spanish architectural contexts, these cases have been cited as evidence that colono ware serving vessels were produced by indigenous potters for Spaniards unable to obtain sufficient quantities of majolica. But in both cases, after migration as refugees and resettlement, the production of colono ware serving vessels increases dramatically to 18-20% of the ceramic assemblage. Furthermore, these vessels are found in large quantities in contexts where architectural and other evidence suggest the occupants were indigenous, and not European. As shown above, the same holds true for Ciudad Vieja, where 17% of the ceramic assemblage is colono ware plates. In all of these cases, indigenous households are enthusiastic consumers of colono wares. And in all three cases, the "indigenous" inhabitants of these communities have been uprooted as refugees, soldiers, servants, or slaves. By contrast, in colonial sites that predate European contact and conquest as previously existing communities, colono ware production is relatively low, and consumption in many cases is largely found in contexts believed to have been created by Spanish colonists. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Text links to all pages at this site are available at the FAMSI INDEX |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||